Disclaimer: This article reflects my personal interpretation and understanding of the ideas presented by Jordan B. Peterson in his lecture Introduction to the Idea of God. It is based on my own assumptions, reflections, and independent research, and does not claim to represent any theological or academic authority. My intention is not to discuss religion, but to explore an intellectual and philosophical angle on the concept of sovereignty and how it connects to questions of responsibility, order, and autonomy in the digital age.

The views expressed here are entirely my own and written in the spirit of curiosity, personal development, and open dialogue.

—

For most of modern history, sovereignty was a word reserved for kings, nations, and divine powers. Today, it has migrated into the digital realm. Governments speak of data sovereignty, organisations demand cloud sovereignty, and regulators debate digital autonomy as if it were a new invention. Yet the word itself carries a much deeper heritage.

I have always been drawn to content that challenges me to think deeper. To develop myself, to learn, and to become a more decent human being. That is why I often watch lectures and interviews from thinkers like Jordan B. Peterson. His lecture Introduction to the Idea of God recently caught my attention, not because of its theological angle, but because of how he describes sovereignty. Not as external power, but as an inner principle – the ability to rule responsibly within a domain while remaining subordinate to higher laws and moral order.

That insight provides an unexpected bridge into the digital age. It suggests that sovereignty, whether human or technological, is never just about control. It is about responsible dominion, the ability to govern a domain while remaining answerable to the principles that make such governance legitimate.

When we speak about digital sovereignty, we are therefore not talking about ownership alone. We are talking about whether our digital systems reflect that same hierarchy of responsibility and whether power remains accountable to the principles it claims to serve.

The ancient logic of rule

Long before the language of “data localization” and “cloud independence”, ancient myths wrestled with the same question: who rules, and under what law?

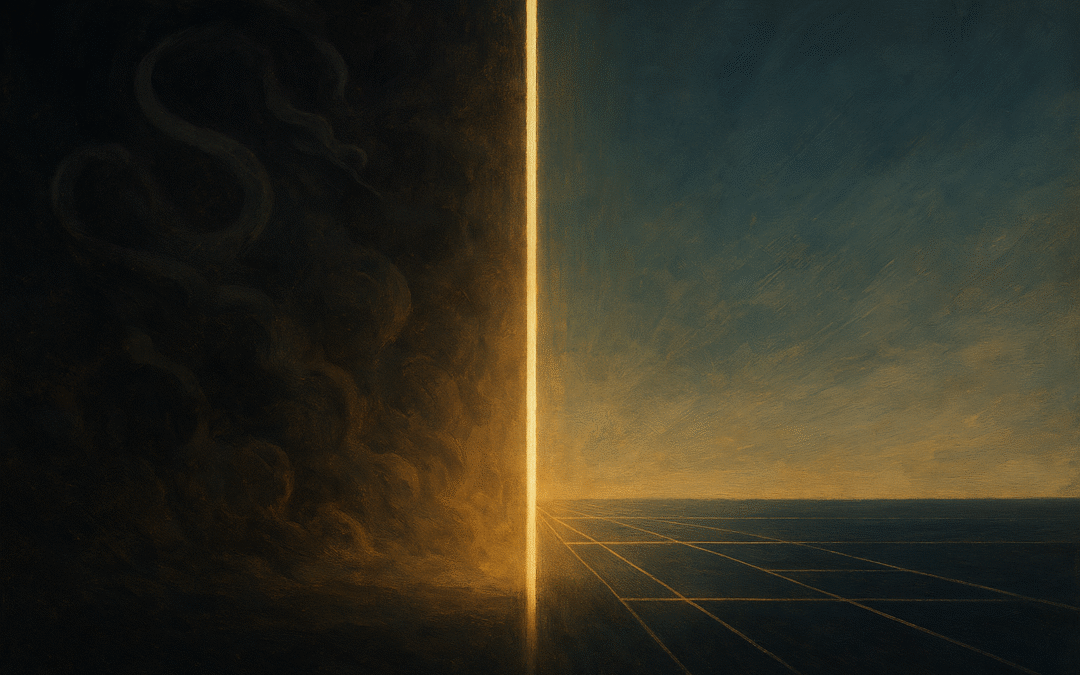

Peterson revisits the Mesopotamian story of Marduk, the god who slays the chaos-monster Tiamat and creates the ordered world from her remains. Marduk becomes king of the gods not because he seizes power, but because he sees clearly (his eyes encircle his head) and speaks truth (his voice creates order). Sovereignty, in this reading, is vision plus articulation, which means that perception and speech transform chaos into structure.

Source: https://mesopotamia.mrdonn.org/marduk.html

That principle later reappears in the Hebrew conception of God as a lawgiver above kings. Even the ruler is subordinate to the law, and even the sovereign must bow to the principle of sovereignty itself. This inversion, that the highest power is bound by what is highest, became the cornerstone of Western political thought and the invisible moral logic behind constitutional democracies.

When power forgets that it is subordinate, it turns into tyranny. When it forgets its responsibility, chaos returns.

From political sovereignty to digital power

Fast-forward to the 21st century. We have entered a world where data centers replace palaces and algorithms rival parliaments. Our digital infrastructures have become the new seat of sovereignty. Whoever controls data, compute, and AI, controls the rhythm of economies and the tempo of societies.

Yet, as Peterson would put it, the psychological pattern remains the same. The temptation for absolute rule, for technical sovereignty without moral subordination, is as old as humanity. When a cloud provider holds the keys to a nation’s data but owes its allegiance to no higher principle than profit, sovereignty decays into dominance. When a government seeks total control over data flows without respecting personal freedom, sovereignty mutates into surveillance.

Therefore, digital sovereignty cannot be achieved by isolation alone. It requires a principle above control and a framework of responsibility, transparency, and trust. Without that, even the most sovereign infrastructure becomes a gilded cage.

Sovereignty as responsibility, not control

Peterson defines sovereignty as rule under law, not rule above it. In the biblical imagination, even God’s power is bound by his word – the principle that creates and limits at the same time. That is the paradox of legitimate sovereignty: its strength comes from restraint.

Applied to technology, this means that a sovereign cloud is sovereign because it binds itself to principle. It protects data privacy, enforces jurisdictional control, and allows auditability not because regulation demands it, but because integrity does.

The European vision of digital sovereignty, from the EU’s Data Act to Gaia-X, is, at its core, an attempt to recreate that ancient alignment between power and rule. It is a collective recognition that technical autonomy without ethical structure leads nowhere. Sovereign infrastructure is not an end in itself but a container for trust.

The danger of absolute sovereignty

Peterson warns that when sovereignty becomes absolute, when a ruler or system recognises no law above itself, catastrophe follows. He points to 20th-century totalitarian regimes where ideology replaced principle and individuals were crushed under the weight of unbounded power.

Our digital landscape carries similar risks. The hyperscaler model, while enabling global innovation, also consolidates an unprecedented concentration of authority. When three or four companies decide how data is stored, how AI models are trained, and which APIs define interoperability, sovereignty becomes fragile. We exchange the chaos of fragmentation for the order of dependence.

Likewise, when nations pursue “data nationalism” without transparency or interoperability, they may protect sovereignty in name but destroy it in spirit. The closed sovereign cloud is the modern equivalent of the paranoid king. Safe behind walls, but blind to the world beyond them.

True sovereignty, Peterson reminds us, requires both vision and speech. You must see beyond your borders and articulate the principles that guide your rule.

Seeing and speaking truth

In Peterson’s cosmology, the sovereign creates order by confronting chaos directly by seeing clearly and speaking truthfully. That process translates elegantly into the digital domain.

To build responsible digital systems, we must first see where our dependencies lie: in APIs, in hardware supply chains, in foreign jurisdictions, in proprietary formats. Sovereignty begins with visibility, with mapping the landscape of control.

Then comes the speech, the articulation of principle. What do we value? Data integrity? Interoperability? Legal transparency? Without speaking those truths, sovereignty becomes mute. The process of defining digital sovereignty is therefore not only political or technical but also linguistic and moral. It requires the courage to define what the higher principle actually is.

In Europe, this articulation is still evolving. The Gaia-X framework, the Swiss Government Cloud initiative, or France’s “Cloud de Confiance” are all attempts to speak sovereignty into existence by declaring that our infrastructure must reflect our societal values, not merely technical efficiency.

The individual at the root of sovereignty

One of Peterson’s most subtle points is that sovereignty ultimately begins in the individual. You cannot have a sovereign nation composed of individuals who refuse responsibility. Likewise, you cannot have a sovereign digital ecosystem built by actors who treat compliance as theatre and trust as a marketing term.

Every architect, policymaker, and operator holds a fragment of sovereignty. The question is whether they act as tyrants within their domain or as stewards under a higher rule. A cloud platform becomes sovereign when its people behave sovereignly and when they balance autonomy with discipline, ownership with humility.

In that sense, digital sovereignty is a psychological project as much as a technical one. It demands integrity, courage, and self-limitation at every level of the stack.

From divine order to digital order

The story of sovereignty, from the earliest myths to the latest regulations, is the same story told in different languages. It is the human struggle to balance power and principle, freedom and responsibility, chaos and order.

Peterson’s interpretation of sovereignty – the ruler who sees and speaks, the individual who stands upright before the highest good – offers a mirror for our technological age. The digital world is the new frontier of chaos. Our infrastructures are its architecture of order. Whether that order remains free depends on whether we remember the ancient rule: even the sovereign must be subordinate to sovereignty itself.

A sovereign cloud, therefore, is not the digital expression of nationalism, but the continuation of an older and nobler tradition. To govern power with conscience, to build systems that serve rather than dominate, to make technology reflect the values of the societies it empowers.

The true measure of sovereignty, digital or divine, lies not in the scope of control but in the depth of responsibility.