Why Workloads Are Really Repatriating to Private Cloud and How to Prepare for AI

In the beginning, renting won. Managed services and elastic capacity let teams move faster than procurement cycles, and the “convenience tax” felt like a bargain. A decade later, many enterprises have discovered what one high-profile cloud exit made clear: The same convenience that speeds delivery can erode margins at scale. That realization is driving a new wave of selective repatriation, moving the right workloads from hyperscale public clouds back to private cloud platforms, while a second force emerges simultaneously. AI is changing what a data center needs to look like. Any conversation about bringing workloads home that ignores AI-readiness is incomplete.

What’s really happening (and what isn’t)

Repatriation today is targeted. IDC’s Server and Storage Workloads Survey found that only ~8-9% of companies plan full repatriation. Most enterprises bring back specific components like production data, backup pipelines, or compute, where economics, latency, or exit risk justify it.

Media coverage has sharpened the picture. CIO.com frames repatriation as strategic workload placement rather than a retreat. InfoWorld’s look at 2025 trends notes rising data-center use even as public-cloud spend keeps growing. Forrester’s 2025 predictions echo the co-existence. Public cloud expands, private cloud thrives alongside it. Hybrid is normal. Sovereignty, cost control, and performance are the levers.

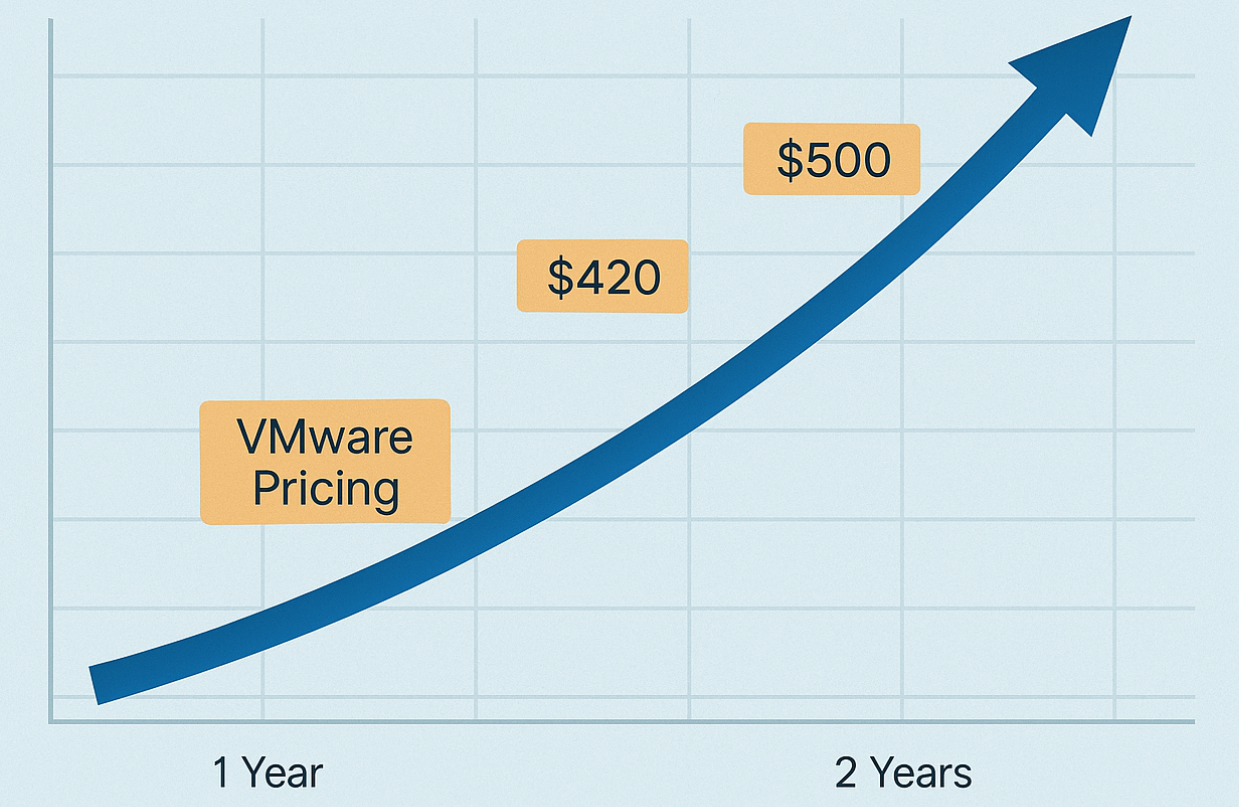

And then there are the headline case studies. 37signals (Basecamp/HEY) publicized their journey off AWS – deleting their account in 2025 after moving storage to on-prem arrays and citing seven-figure annual savings on S3 alone. Whether or not your estate looks like theirs, it crystallized the idea that the convenience premium can outgrow its value at scale.

Why the calculus changed

Unit economics at scale. Per-unit cloud pricing that felt fine at 100 TB looks different at multiple PB, especially once you add data egress, cross-AZ traffic, and premium managed services. Well-understood examples (Dropbox earlier) show material savings when high-volume, steady-state workloads move to owned capacity.

Performance locality and control. Some migrations lifted and shifted latency-sensitive systems into the wrong place. Round-trip times, noisy neighbors, or throttling can make the public cloud an expensive place to be for chatty, tightly coupled apps. Industry coverage repeatedly points to “the wrong workload in the wrong spot” as a repatriation driver.

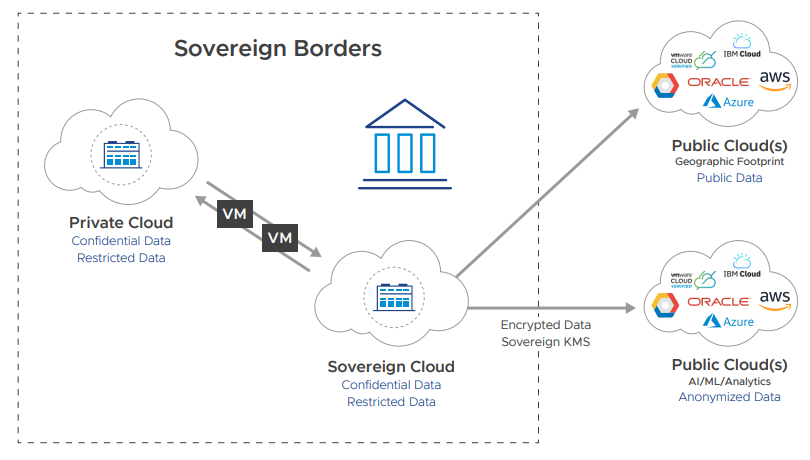

Sovereignty and exit risk. Regulated industries must reconcile GDPR/DORA-class obligations and the US CLOUD Act with how and where data is processed. The mid-market is echoing this too. Surveys show a decisive tilt toward moving select apps for compliance, control, and resilience reasons.

FinOps maturity. After a few budgeting cycles, many teams have better visibility into cloud variability and the true cost of managed services. Some will optimize in-place, others will re-platform components where private cloud wins over a 3-5 year horizon.

Don’t bring it back to a 2015 data center

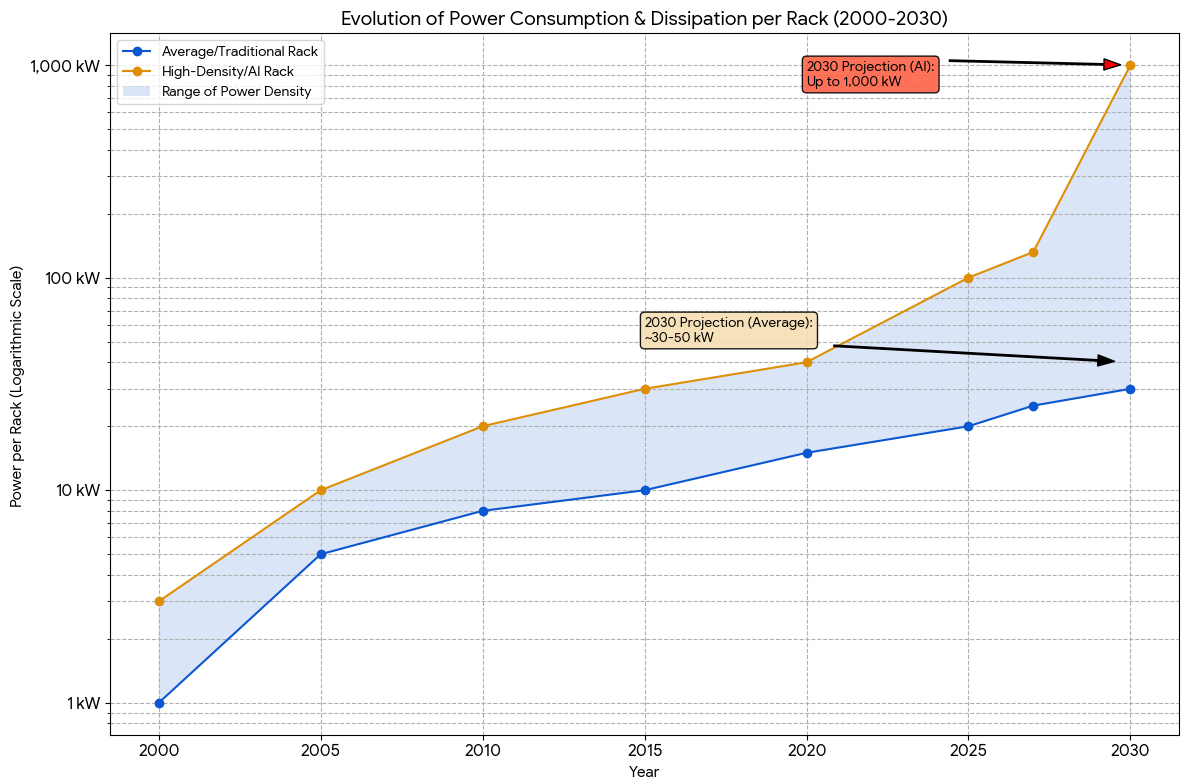

Even if you never plan to train frontier models, AI has changed the physical design targets. Racks that once drew 8-12 kW now need to host 30-50 kW routinely and 80-100+ kW for dense GPU nodes. Next-gen AI racks can approach 1 MW per rack in extreme projections.

Image credit: Lennox Data Center Solutions

Air alone won’t be enough. Direct-to-Chip or immersion liquid cooling, higher-voltage distribution, and smarter power monitoring become minimum requirements. European sites face grid constraints that make efficiency and modular growth plans essential.

This is the retrofit conversation many teams are missing. If you repatriate analytics, vector databases, or LLM inference and can’t cool them, you’ve just traded one bottleneck for another.

How the analysts frame the decision

A fair reading across recent coverage lands on three points:

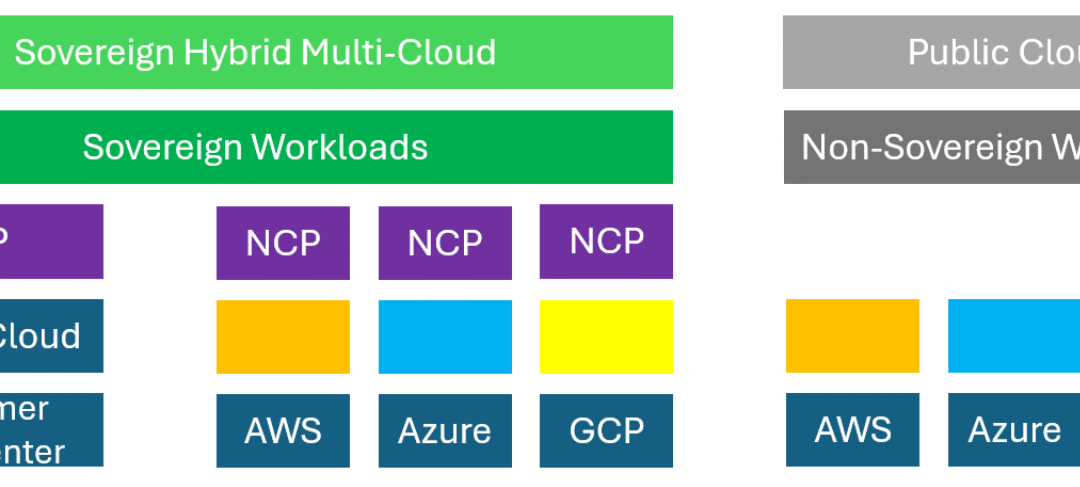

- Hybrid wins. Public cloud spend grows, and so do private deployments, because each has a place. Use the public cloud for burst, global reach, and cutting-edge managed AI services. Use the private cloud for steady-state, regulated (sovereign), chatty, or data-gravity workloads.

- Repatriation is selective. It’s about fit. Data sets with heavy egress, systems with strict jurisdiction rules, or platforms that benefit from tight locality are top candidates.

- AI is now a first-order constraint. Power, cooling, and GPU lifecycle management change the platform brief. Liquid cooling and higher rack densities stop being exotic and become practical requirements.

Why Nutanix is the safest private cloud bet for enterprises and the regulated world

If you are going to own part of the stack again, two things matter: Operational simplicity and future-proofing. This is where Nutanix stands out.

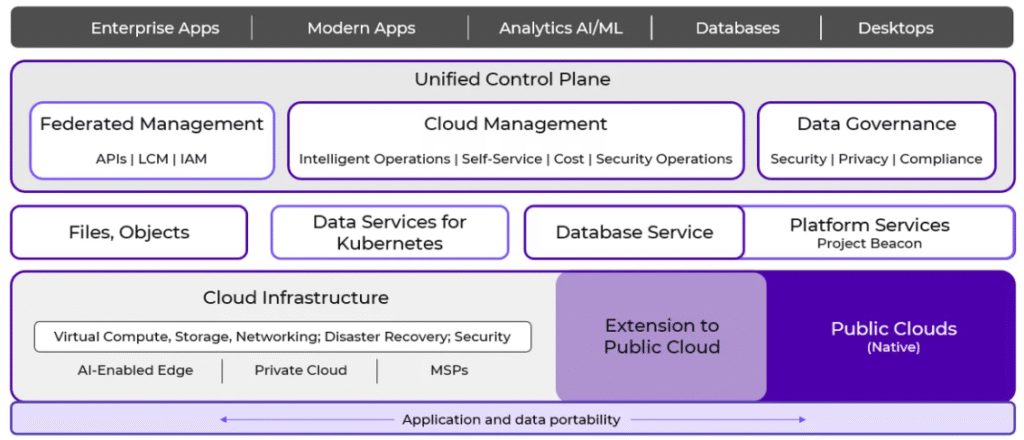

A single control plane for private, hybrid, and edge. Nutanix Cloud Platform (NCP) lets you run VMs, files/objects, and containers with one operational model across on-prem and public cloud extensions. It’s built for steady-state enterprise workloads and the messy middle of hybrid.

Kubernetes without the operational tax. Nutanix Kubernetes Platform (NKP), born from the D2iQ acquisition, prioritizes day-2 lifecycle management, policy, and consistency across environments. If you are repatriating microservices or building AI micro-stacks close to data, this reduces toil.

AI-ready from the hypervisor up. AHV supports NVIDIA GPU passthrough and vGPU, and Nutanix has published guidance and integrations for NVIDIA AI Enterprise. That means you can schedule, share, and secure GPUs for training or inference alongside classic workloads, instead of creating a special-case island.

Data services with immutability. If you bring data home, protect it. Nutanix Unified Storage (NUS) provides WORM/immutability and integrates with leading cyber-recovery vendors, giving you ransomware-resilient backups and object locks without bolt-on complexity.

Enterprise AI without lock-in. Nutanix Enterprise AI (NAI) focuses on building and operating model services on any CNCF-certified Kubernetes (on-prem, at the edge, or in cloud) so you keep your data where it belongs while retaining choice over models and frameworks. That aligns directly with sovereignty programs in government and regulated industries.

You get a private cloud that behaves like a public cloud where it matters, including lifecycle automation, resilience, and APIs. Under your control and jurisdiction.

Designing the landing zone

On day zero, deploy NCP as your substrate with AHV and Nutanix Unified Storage. Enable GPU pools on hosts that will run inference/training, and integrate NKP for container workloads. Attach immutable backup policies to objects and align with your chosen cyber-recovery stack. As you migrate, standardize on one identity plane and network policy model so VMs and containers are governed the same way. When you are ready to operationalize AI services closer to data, layer NAI to package and run model APIs with the same lifecycle tooling you already know.

The bottom line?

Repatriation is the natural correction after a decade of fast, sometimes indiscriminate, lift-and-shift, and not an anti-cloud movement. The best operators are recalibrating placement. AI turns this from a pure cost exercise into an infrastructure redesign. You can’t bring modern workloads home to a legacy room.

If you want the private side of that hybrid story without rebuilding a platform team from scratch, Nutanix is the safe choice. You get a single control plane for virtualization, storage, and Kubernetes, immutable data services for cyber-resilience, proven GPU support, and an AI stack that respects your sovereignty choices. That’s how you pay for convenience once, not forever, and how you make the next decade less about taxes and more about outcomes.