Switching enterprise platforms isn’t like swapping cars and more like deciding to change the side of the road you drive on while keeping all the existing roads, intersections, traffic lights, and vehicles in motion. The complexity comes from rethinking the entire system around you, from driver behaviour to road markings to the way the city is mapped.

That’s exactly what it feels like when an enterprise tries to replace a long-standing platform or add a new one to an already complex mix. On slides, it’s about agility, portability, and choice. In reality, it’s about untangling years of architectural decisions, retraining teams who have mastered the old way of working, and keeping the business running without any trouble while the shift happens.

Every enterprise carries its own technological history. Architectures have been shaped over years by the tools, budgets, and priorities available at the time, and those choices have solidified into layers of integrations, automations, operational processes, and compliance frameworks. Introducing a new platform or replacing an old one isn’t just a matter of deploying fresh infrastructure. Monitoring tools may only talk to one API. Security controls might be tightly bound to a specific identity model. Ticketing workflows could be designed entirely around the behaviour of the current environment. All of this has to be unpicked and re-stitched before a new platform can run production workloads with confidence.

The human element plays an equally large role. Operational familiarity is one of the most underestimated forms of lock-in. Teams know the details of the current environment, how it fails, and the instinctive fixes that work. Those instincts don’t transfer overnight, and the resulting learning curve can look like a productivity dip in the short term. Something most business leaders are reluctant to accept. Applications also rarely run in isolation. They rely on the timing, latency, and behaviours of the platform beneath them. A database tuned perfectly in one environment might misbehave in another because caching works differently or network latency is just a little higher. Automation scripts often carry hidden assumptions too, which only surface when they break.

Adding another cloud provider or platform to the mix can multiply complexity rather than reduce it. Each one brings its own operational model, cost reporting, security framework, and logging format. Without a unified governance approach, you risk fragmentation – silos that require separate processes, tools, and people to manage. And while the headline price per CPU or GB (or per physical core) might look attractive, the true cost includes migration effort, retraining, parallel operations, and licensing changes. All of this competes with other strategic projects for budget and attention.

Making Change Work in Practice

No migration is ever frictionless, but it doesn’t have to be chaotic. The most effective approach is to stop treating it as a single, monolithic event. Break the journey into smaller stages, each delivering its own value.

Begin with workloads that are low in business risk but high in operational impact. This category often includes development and test environments, analytics platforms processing non-sensitive data, or departmental applications that are important locally but not mission-critical for the entire enterprise. Migrating these first provides a safe but meaningful proving ground. It allows teams to validate network designs, security controls, and operational processes in the new platform without jeopardising critical systems.

Early wins in this phase build confidence, uncover integration challenges while the stakes are lower, and give leadership tangible evidence that the migration strategy is working. They also provide a baseline for performance, cost, and governance that can be refined before larger workloads move.

Build automation, governance, and security policies to be platform-agnostic from the start, using open standards, modular designs, and tooling that works across multiple environments. And invest early in people: cross-train them, create internal champions, and give them the opportunity to experiment without the pressure of immediate production deadlines. If the new environment is already familiar by the time it goes live, adoption will feel less like a disruption and more like a natural progression.

From Complex Private Clouds to a Unified Platform

Consider an enterprise running four separate private clouds: three based on VMware – two with vSphere Foundation and one with VMware Cloud Foundation including vSphere Kubernetes Services (VKS), and one running Red Hat OpenShift on bare metal. Each has its own tooling, integrations, and operational culture.

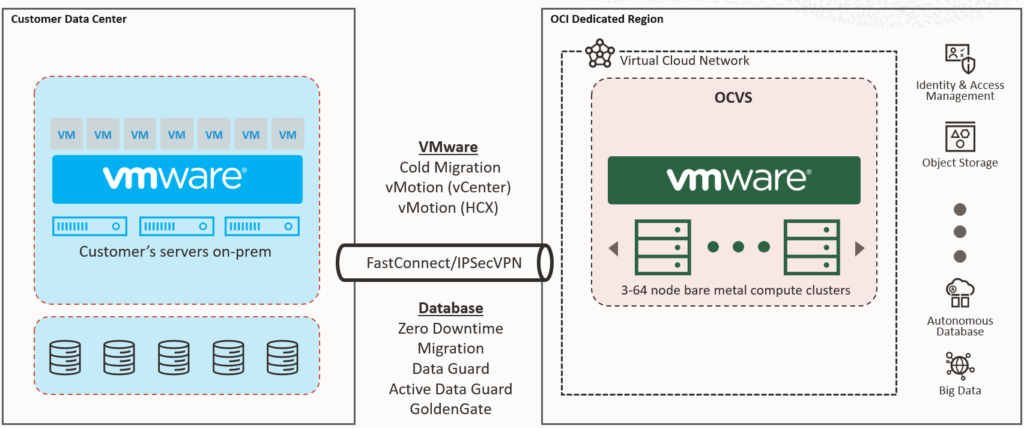

Migrating the VMware workloads to Oracle Cloud VMware Solution (OCVS) inside an OCI Dedicated Region allows workloads to be moved with vMotion or replication, without rewriting automation or retraining administrators. It’s essentially another vSphere cluster, but one that scales on demand and is hosted in facilities under your control.

The OpenShift platform can also move into the same Dedicated Region, either as a direct lift-and-shift onto OCI bare metal or VMs, or as part of a gradual transition toward OCI’s native Kubernetes service (OKE). This co-location enables VMware, OpenShift, and OCI-native workloads to run side by side, within the same security perimeter, governance model, and high-speed network. It reduces fragmentation, simplifies scaling, and allows modernisation to happen gradually instead of in a high-risk “big bang” migration.

Unifying Database Platforms

In most large enterprises, databases are distributed across multiple platforms and technologies. Some are Oracle, some are open source like PostgreSQL or MySQL, and others might be Microsoft SQL Server. Each comes with its own licensing, tooling, and operational characteristics.

An OCI Dedicated Region can consolidate all of them. Oracle databases can move to Exadata Database Service or Autonomous Database for maximum performance, scalability, and automation. Non-Oracle databases can run on OCI Compute or as managed services, benefitting from the same network, security, and governance as everything else.

This consolidation creates operational consistency with one backup strategy, one monitoring approach, one identity model across all database engines. It reduces hardware sprawl, improves utilisation, and can lower costs through programmes like Oracle Support Rewards. Just as importantly, it positions the organisation for gradual application modernization, without being forced into rushed timelines.

A Business Case Built on More Than Cost

The value in this approach comes from the ability to run new workloads, whether VM-based, containerized, or fully cloud-native, on the same infrastructure without waiting for new procurement cycles. It’s about strategic control by keeping infrastructure and data within your own facilities, under your jurisdiction, while still accessing the full capabilities of a hyperscale cloud. And it’s about flexibility. Moving VMware first, then OpenShift, then databases, and modernizing over time, with each step delivering value and building confidence for the next.

When done well, this isn’t just a platform change. It’s a simplification of the entire environment, an upgrade in capabilities, and a long-term investment in agility and control.