Sovereignty in the cloud is often treated as a cost. Something that slows innovation, complicates operations, and makes infrastructure more expensive. But for governments, critical industries, and regulated enterprises, sovereignty is the basis of resilience, compliance, and long-term autonomy. Hence, sovereignty is not seen as a burden. The way a provider positions sovereignty reveals a lot about how they see the balance between global scale and local control.

Some platforms like Oracle’s EU Sovereign Cloud show that sovereignty doesn’t have to come at the expense of capability. It delivers the same services, the same pricing, and operates entirely with EU-based staff. Nutanix pushes the idea even further with its distributed cloud operating model, proving that sovereignty and value can reinforce each other rather than clash.

Microsoft’s Framing

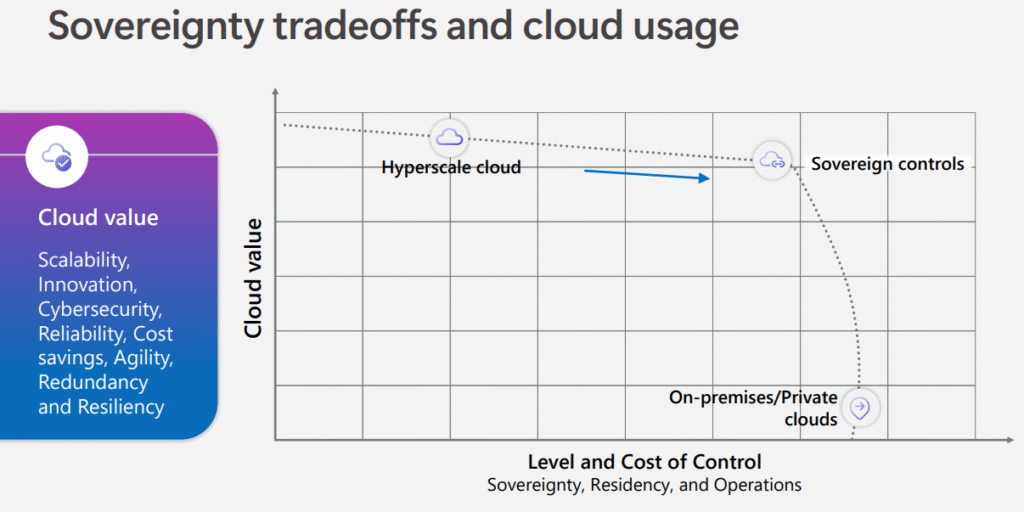

In Microsoft’s chart, the hyperscale cloud sits on the far left of the spectrum. Standard Azure and Microsoft 365 are presented as delivering only minimal sovereignty, little residency choice, and almost no operational control. The upside, in their telling, is that this model maximizes “cloud value” through global scale, innovation, and efficiency.

Move further to the right and you encounter Microsoft’s sovereign variants. Here, they place offerings such as Azure Local with M365 Local and national partner clouds like Delos in Germany or Bleu in France. These are designed to deliver more sovereignty and operational control by layering in local staff, isolated infrastructure, and stricter national compliance. Yet the framing is still one of compromise. As you gain sovereignty, you are told that some of the value of the hyperscale model inevitably falls away.

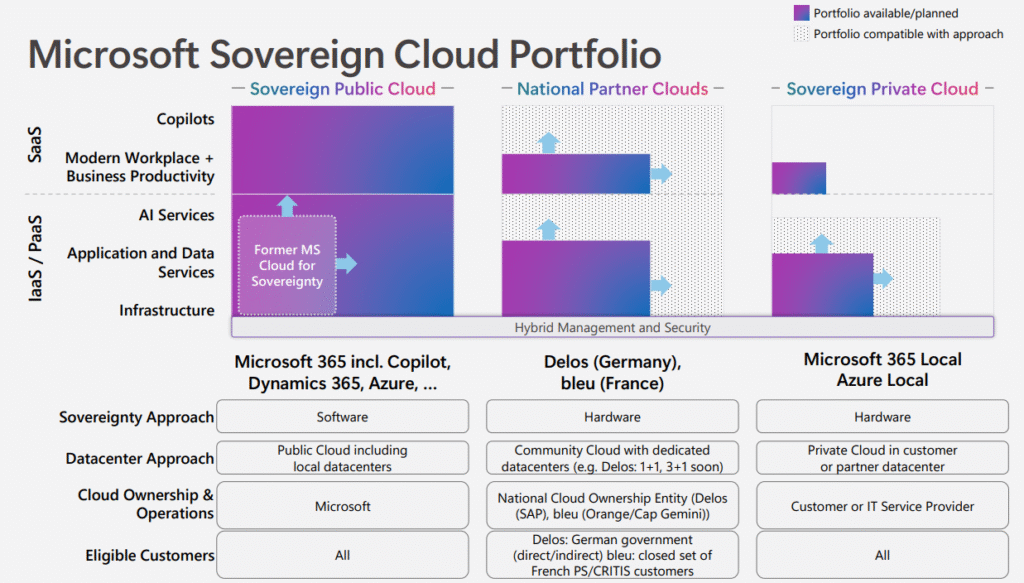

Microsoft’s Sovereign Cloud Portfolio

To reinforce this point, Microsoft presents a portfolio of three models. The first is the Sovereign Public Cloud, which is owned and operated directly by Microsoft. Data remains in Europe, and customers get software-based sovereignty controls such as “Customer Lockbox” or “Confidential Computing”. It runs in Microsoft’s existing datacenters and doesn’t require migration, but it is still, at its core, a hyperscale cloud with policy guardrails added on top.

The second model is the Sovereign Private Cloud. This is customer-owned or partner-operated, running on Azure Local and Microsoft 365 Local inside local data centers. It can be hybrid or even disconnected, and is validated through Microsoft’s traditional on-premises server stack such as Hyper-V, Exchange, or SharePoint. Here, sovereignty increases because customers hold the operational keys, but it is clearly a departure from the hyperscale simplicity.

Finally, there are the National Partner Clouds, built in cooperation with approved local entities such as SAP for Delos in Germany or Orange and Cap Gemini for Bleu in France. These clouds are fully isolated, meet the most stringent government standards like SecNumCloud in France, and are aimed at governments and critical infrastructure providers. In Microsoft’s portfolio, this is the most sovereign option, but also the furthest away from the original promise of the hyperscale cloud.

On paper, this portfolio looks broad. But the pattern remains: Microsoft treats sovereignty as something that adds control at the expense of cloud value.

What If We Reframe the Axes From “Cloud Value” to “Business Value”?

That framing makes sense if you are a hyperscaler whose advantage lies in global scale. But it doesn’t reflect how governments, critical infrastructure providers, or regulated enterprises measure success. If we shift the Y-axis away from “cloud value” and instead call it “business value”, the story changes completely. Business value is about resilience, compliance, cost predictability, reliable performance in local contexts, and the flexibility to choose infrastructure and partners that meet strategic needs.

The X-axis also takes on a different character. Instead of seeing sovereignty, residency, and operations as a cost or a burden, they become assets. The more sovereignty an organization can exercise, the more it can align its IT operations with national policies, regulatory mandates, and its own resilience strategies. In this reframing, sovereignty is not a trade-off, but a multiplier.

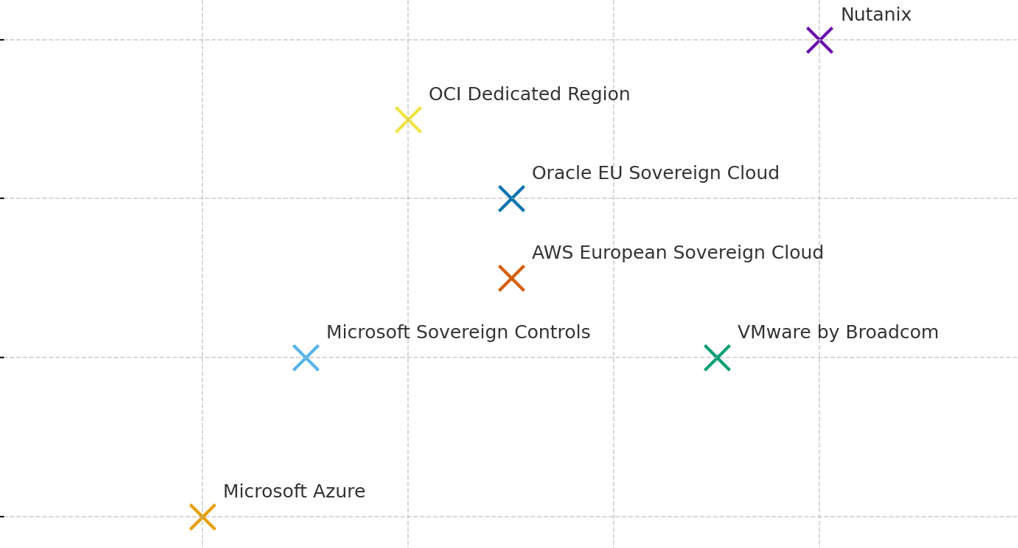

What the New Landscape Shows

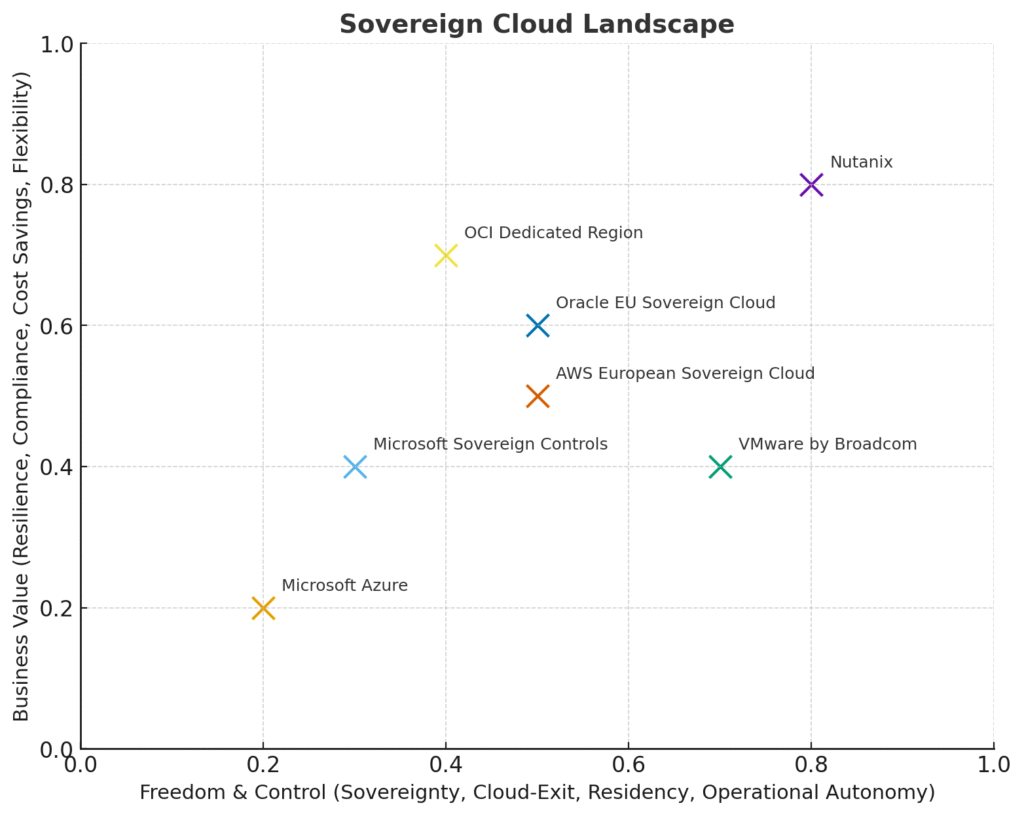

Once you adopt this perspective, the map of cloud providers looks very different.

Please note: Exact positions on such a chart are always debatable, depending on whether you weigh ecosystem, scale, or sovereignty highest. 🙂

Microsoft Azure sits in the lower left, offering little in terms of sovereignty or control and, as a result, little real business value for sectors that depend on compliance and resilience. Adding Microsoft’s so-called sovereign controls moves the position slightly upward and to the right, but it still remains closer to enhanced compliance than genuine sovereignty. AWS’s European Sovereign Cloud lands in the middle, reflecting its cautious promises, which are a step toward sovereignty but not yet backed by deep operational independence.

Oracle’s EU Sovereign Cloud moves higher because it combines full service parity with the regular Oracle Cloud, identical pricing, and EU-based operations, making it a credible sovereign choice without hidden compromises. OCI Dedicated Region provides strong business value in a customer’s location, but since operations remain largely in Oracle’s hands, it offers less direct control than something like VMware. VMware by Broadcom sits further to the right thanks to the control it gives customers who run the stack themselves, but its business value is dragged down by complexity, licensing issues, and legacy cost.

The clear outlier is Nutanix, rising toward the top-right corner. Its distributed cloud model spanning on-prem, edge, and multi-cloud maximizes control and business value compared to most peers. Yes, Nutanix is not flawless, and yes, Nutanix lacks the massive partner ecosystem and developer gravity of hyperscalers, but for organizations prioritizing sovereignty, it comes closest to the “ideal zone”.

Conclusion

The lesson here is simple. Sovereignty is always a matter of perspective. For a hyperscaler, it looks like a tax on efficiency. For governments, banks, hospitals, or critical industries, it is the very foundation of value. For enterprises trying to reconcile global ambitions with local obligations, sovereignty is not a drag on innovation but the way to ensure autonomy, resilience, and compliance.

Microsoft’s chart is not technically wrong, but it is incomplete. Once you redefine the axes around real-world business priorities, you see that sovereignty does not reduce value. For many organizations, it is the only way to maximize it – though the exact balance point will differ depending on whether your priority is scale, compliance, or operational autonomy.