Cloud Repatriation and the Growth Paradox of Public Cloud IaaS

Over the past two years, a new narrative has taken hold in the cloud market. No, it is not always about sovereign cloud. 🙂 Headlines talk about cloud repatriation – nothing really new, but it is still out there. CIOs speak openly about pulling some workloads back on-premises. Analysts write about organizations “correcting” some earlier cloud decisions to optimize cloud spend. In parallel, hyperscalers themselves now acknowledge that not every workload belongs in the public cloud.

And yet, when you look at the data, you will find a paradox.

IDC and Gartner both project strong, sustained growth in public cloud IaaS spending over the next five years. Not marginal growth and sign of stagnation. But a market that continues to expand at scale, absorbing more workloads, more budgets, and more strategic relevance every year.

At first glance, these two trends appear contradictory. If organizations are repatriating workloads, why does public cloud IaaS continue to grow so aggressively? The answer lies in understanding what is actually being repatriated, what continues to move to the cloud, and how infrastructure constraints are reshaping decision-making in ways that are often misunderstood.

Cloud Repatriation Is Real, but Narrower Than the Narrative Suggests

Cloud repatriation is not a myth. It is happening, but it is also frequently misinterpreted.

Most repatriation initiatives are highly selective. They focus on predictable, steady-state workloads that were lifted into the public cloud under assumptions that no longer hold. Cost transparency has improved, egress fees are better understood and operating models have matured. What once looked flexible and elastic is now seen as expensive and operationally inflexible for certain classes of workloads.

What is rarely discussed is that repatriation does not mean “leaving the cloud”, but I have to repeat it again: It means rebalancing. Meaning, that trganizations are not abandoning public cloud IaaS as a concept. They are just refining their usage of it.

At the same time, some new workloads continue to flow into public cloud environments. Digital-native applications, analytics platforms, some AI pipelines, globally distributed services, and short-lived experimental environments still align extremely well with public cloud economics and operating models. These workloads were not part of the original repatriation debate, and they seem to be growing faster than traditional workloads are being pulled back.

This is how both statements can be true at the same time. Cloud repatriation exists, and public cloud IaaS continues to grow.

The Structural Drivers Behind Continued IaaS Growth

Public cloud IaaS growth is not driven by blind enthusiasm anymore. It is driven by structural forces that have little to do with fashion and everything to do with constraints.

One of the most underestimated factors is time. Building infrastructure takes time and procuring hardware takes time as well. Scaling data centers takes time and many organizations today are not choosing public cloud because it is cheaper or “better”, but because it is available now.

This becomes even more apparent when looking at the hardware market right now.

Hardware Shortages and Rising Server Prices Change the Equation

The infrastructure layer beneath private clouds has suddenly become a bottleneck. Server lead times have increased, GPU availability is constrained and prices for enterprise-grade hardware continue to rise, driven by supply chain pressures, higher component costs, and growing demand from AI workloads.

For organizations running large environments, this introduces a new type of risk. Capacity planning is a logistical problem and no longer just a financial exercise anymore. Even when budgets are approved, hardware may not arrive in time. That is the new reality.

In this context, public cloud data centers represent something extremely valuable: pre-existing capacity. Hyperscalers have already made the capital investments and they already operate at scale. From the customer perspective, infrastructure suddenly looks abundant again.

This is why many organizations currently consider shifting workloads to public cloud IaaS, even if they were previously skeptical. It became a pragmatic response to scarcity.

The Flawed Assumption: “Just Use Public Cloud Instead of Buying Servers”

However, this line of thinking often glosses over a critical distinction.

Many of these organizations do not actually want “cloud-native” infrastructure, if we are being honest here. What they want is physical capacity – They want compute, storage, and networking under predictable performance characteristics. In other words, they want some VMs and bare metal.

Buying servers allows organizations to retain architectural freedom. It allows them to choose their operating system or virtualization stack, their security model, their automation tooling, and their lifecycle strategy. Public cloud IaaS, by contrast, delivers abstraction, but at the cost of dependency.

When organizations consume IaaS services from hyperscalers, they implicitly accept constraints around instance types, networking semantics, storage behavior, and pricing models. Over time, this shapes application architectures and operational processes. The usage of such services suddenly became a lock-in.

Bare Metal in the Public Cloud Is Not a Contradiction

Interestingly, the industry has started to converge on a hybrid answer to this dilemma: bare metal in the public cloud.

Hyperscalers themselves offer bare-metal services. This is an acknowledgment that not all customers want fully abstracted IaaS. Some want physical control without owning physical assets. It is simple as that.

But bare metal alone is not enough. Without a consistent cloud platform on top, bare-metal in the public cloud becomes just another silo. You gain performance and isolation, but you lose portability and operational consistency.

Nutanix Cloud Clusters and the Reframing of IaaS

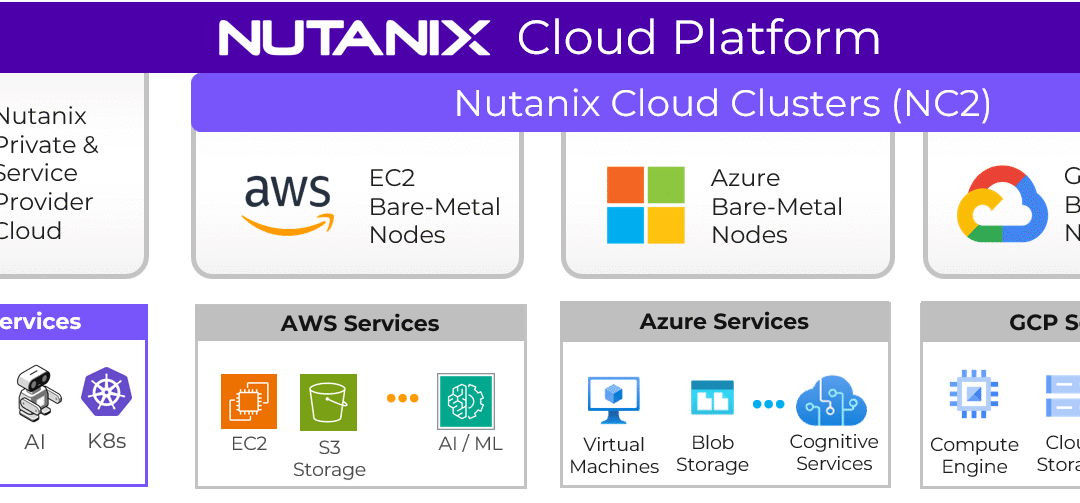

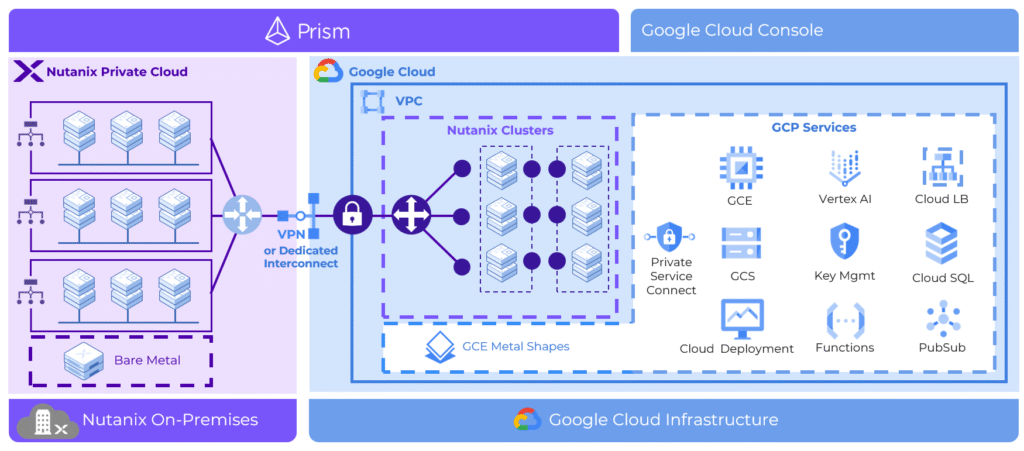

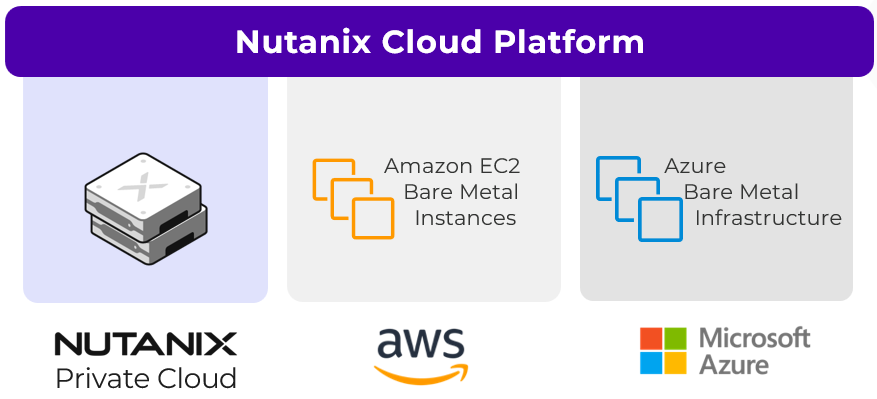

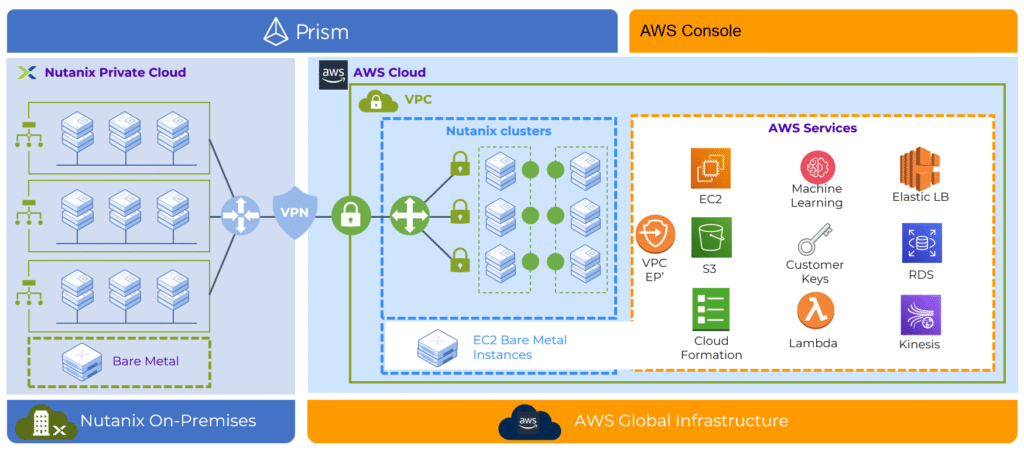

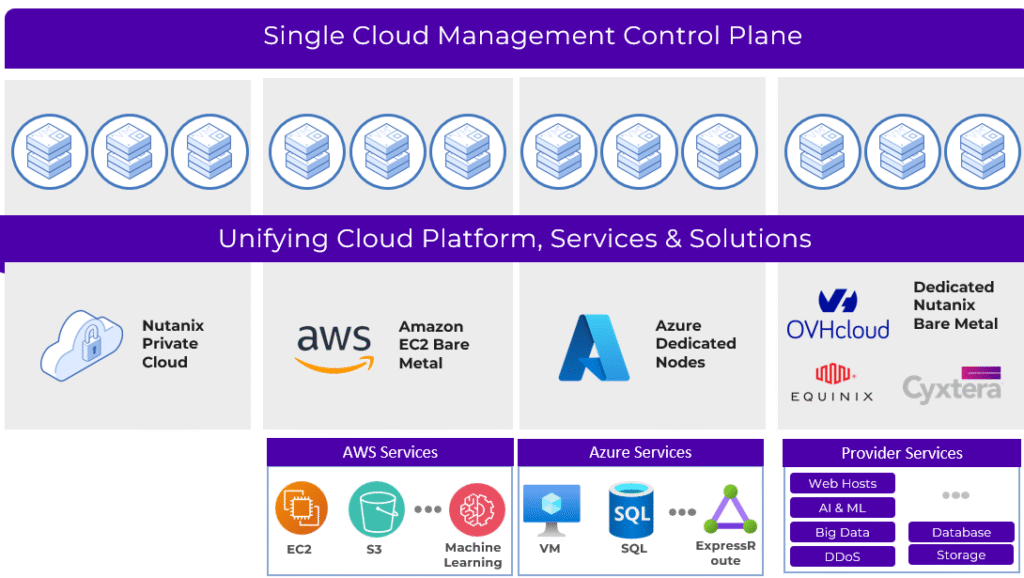

Nutanix Cloud Platform running on AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud through NC2 (Nutanix Cloud Clusters) introduces a different interpretation of public cloud IaaS.

Instead of consuming hyperscaler-native IaaS primitives, customers deploy a full private cloud stack on bare-metal instances in public cloud data centers. From an architectural perspective, this is a subtle but profound difference.

Customers still benefit from the hyperscaler’s global footprint and hardware availability and they still avoid long procurement cycles, but they do not surrender control of their cloud operating model. The same Nutanix stack runs on-premises and in public cloud, with the same APIs, the same tooling, and the same governance constructs.

Workload Mobility as the Missing Dimension

The most underappreciated benefit of this approach is workload mobility.

In a cloud-native bare-metal deployment tied directly to hyperscaler services, workloads tend to become anchored, migration becomes complex, and exit strategies are theoretical at best.

With NC2, workloads are portable by design. Virtual machines and applications can move between on-premises environments and public cloud (or a service provider cloud) bare-metal clusters without refactoring. In practical terms, this means organizations can use public cloud capacity tactically rather than strategically committing to it. Capacity shortages, temporary demand spikes, regional requirements, or regulatory constraints can be addressed without redefining the entire infrastructure strategy.

This is something traditional IaaS does not offer, and something pure bare-metal consumption does not solve on its own.

Reconciling the Two Trends

When viewed through this lens, the contradiction between cloud repatriation and public cloud IaaS growth disappears.

Public cloud is growing because it solves real problems: availability, scale, and speed. Repatriation is happening because not all problems require abstraction, and not all workloads benefit from cloud-native constraints.

The future is not a reversal of cloud adoption. It is a maturation of it.

Organizations are asking how to use public clouds without losing control. Platforms that allow them to consume cloud capacity while preserving architectural independence are not an alternative to IaaS growth and they are one of the reasons that growth can continue without triggering the next wave of regret-driven repatriation.

What complicates this picture further is that even where public cloud continues to grow, many of its original economic promises are now being questioned again.

The Broken Promise of Economies of Scale

One of the foundational assumptions behind public cloud adoption was economies of scale. The logic seemed sound. Hyperscalers operate at a scale no enterprise could ever match. Massive data centers, global procurement power, highly automated operations. All of this was expected to translate into continuously declining unit costs, or at least stable pricing over time.

That assumption has not materialized as we know by now.

If economies of scale were truly flowing through to customers, we would not be witnessing repeated price increases across compute, storage, networking, and ancillary services. We would not see new pricing tiers, revised licensing constructs, or more aggressive monetization of previously “included” capabilities. The reality is that public cloud pricing has moved in one direction for many workloads, and that direction is up.

This does not mean hyperscalers are acting irrationally. It means the original narrative was incomplete. Yes, scale does reduce certain costs, but it also introduces new ones. That is also true for new innovations and services. Energy prices, land, specialized hardware, regulatory compliance, security investments, and the operational complexity of running globally distributed platforms all scale accordingly. Add margin expectations from capital markets, and the result is not a race to the bottom, but disciplined price optimization.

For customers, however, this creates a growing disconnect between expectation and reality.

When Forecasts Miss Reality

More than half of organizations report that their public cloud spending diverges significantly from what they initially planned. In many cases, the difference is not marginal. Budgets are exceeded, cost models fail to reflect real usage patterns, optimization efforts lag behind application growth.

What is often overlooked is the second-order effect of this divergence. Over a third of organizations report that cloud-related cost and complexity issues directly contribute to delayed projects. Migration timelines slip, modernization initiatives stall, and teams slow down not because technology is unavailable, but because financial and operational uncertainty creeps into every decision.

Commitments, Consumption, and a Structural Risk

Most large organizations do not consume public cloud on a purely on-demand basis. They negotiate commitments, look at reserved capacity, and spend-based discounts. These are strategic agreements designed to lower unit costs in exchange for predictable consumption.

These agreements assume one thing above all else: that workloads will move. They HAVE TO move.

When migrations slow down, a new risk pops up. Organizations fail to reach their committed consumption levels, because they cannot move workloads fast enough. Legacy architectures, migration complexity, skill shortages, and governance friction all play a role.

The consequence is subtle but severe. Committed spend still has to be paid and because of that future negotiations become weaker. The organization enters the next contract cycle with a track record of underconsumption, reduced leverage, and less credibility in forecasting.

In effect, execution risk turns into commercial risk.

This dynamic is rarely discussed publicly, but it is increasingly common in private conversations with CIOs and cloud leaders. The challenge is no longer whether the public cloud can scale, but whether the organization can.

Speed of Migration as an Economic Variable

At this point, migration speed stops being a technical metric and becomes an economic one. The faster workloads can move, the faster negotiated consumption levels can be reached. The slower they move, the more value leaks out of cloud agreements.

This is where many cloud-native migration approaches struggle. Refactoring takes time and re-architecting applications is expensive. Not every workload is a candidate for transformation under real-world constraints.

As a result, organizations are caught between two pressures. On one side, the need to consume public cloud capacity they have already paid for. On the other hand, the inability to move workloads quickly without introducing unacceptable risk.

NC2 as a Consumption Accelerator, Not a Shortcut

This is where Nutanix Cloud Platform with NC2 changes the conversation.

By allowing organizations to run the same private cloud stack on bare metal in AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud, NC2 removes one of the biggest bottlenecks in migration programs: The need to change how workloads are built and operated before they can move.

Workloads can be migrated as they are, operating models remain consistent, governance does not have to be reinvented, and teams do not need to learn a new infrastructure paradigm under time pressure. It’s all about efficiency and speed.

Faster migrations mean workloads start consuming public cloud capacity earlier and the negotiated consumption targets suddenly become achievable. Commitments turn into realized value rather than sunk cost, and the organization regains control over both its migration timeline and its commercial position.

Reframing the Role of Public Cloud

In this context, NC2 is not an alternative to public cloud economics, but a mechanism to actually realize them.

Public cloud providers assume customers can move fast. In reality, many customers cannot, not because they resist change, but because change takes time. Platforms that reduce friction between private and public environments do not undermine cloud strategies. They are here to stabilize them. And they definitely can!

The uncomfortable truth is that economies of scale alone do not guarantee better outcomes for customers, execution does. And execution, in large enterprises, depends less on ideal architectures and more on pragmatic paths that respect existing realities.

When those paths exist, public cloud growth and cloud repatriation stop being opposing forces. They become two sides of the same maturation process, one that rewards platforms designed not just for scale, but for transition.