Beyond the Price Tag – Why Organizations Choose Nutanix

In many customer conversations today, the discussion about Nutanix starts in a very pragmatic place: price.

Before we get the chance to talk about architecture, automation, or hybrid cloud strategies, most organizations first want to answer a simpler question: Can we even afford this option? Only once that hurdle is cleared does the real conversation begin. That is the moment when customers start asking a different question: Is it worth spending our time on this platform?

And that shift in perspective is important, because the current market situation is very different from just a few years ago.

For more than a decade, the virtualization market followed a relatively stable pattern. Many organizations standardized on a single hypervisor/platform and built their operational models, processes, and skill sets around it. The question was rarely which hypervisor to choose but more about which edition or which bundle to buy. The platform decision itself was largely settled.

That stability is gone.

Since the licensing and pricing changes in the VMware ecosystem in 2024, many organizations have been forced to rethink assumptions that had been in place for years. Renewal discussions suddenly became strategic decisions and budget forecasts were no longer predictable. In some cases, the cost increases were large enough to trigger board-level attention. Yes, and sometimes even attract political attention.

But price is only one part of the story.

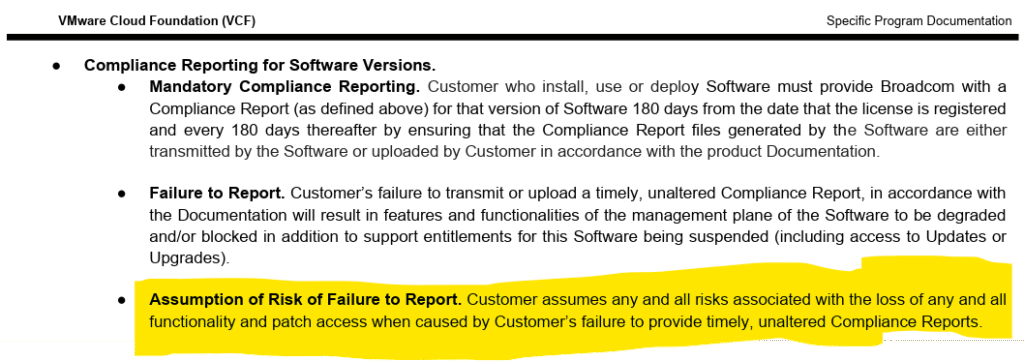

Many customers also question the long-term direction of the platform on which they built their data centers. They are asking themselves whether the vendor’s strategic priorities still align with their own, and they are looking at consolidation in the industry, reduced product portfolios, and new licensing models, and they are wondering what that means for their own autonomy.

As a result, the conversation has shifted from optimization to re-evaluation.

Instead of finetuning an existing environment, many organizations are now exploring a wide spectrum of alternatives. Hyper-V, HPE VM Essentials, Proxmox, Scale Computing, and open-source stacks. Niche hypervisors and even container-first approaches. The list is long, and in many cases, the evaluation is driven less by feature comparisons and more by strategic considerations.

What is interesting in these discussions is the level of pragmatism.

Most customers are very clear about one thing: they know that VMware still offers one of the most mature and feature-rich stack on the market, but they also admit that they do not actually use all of those features. In some environments, large parts of the advanced functionality have been sitting idle for years.

So the goal is no longer to replicate the past environment in every technical detail.

Customers are willing to accept trade-offs. They do not need the most sophisticated dashboards nor do they need every integration or advanced automation capability. If they can move 80 or 90 percent of their workloads to a new platform, that is already a success. The remaining cases can be handled separately.

This is where a new mindset becomes visible: fail fast, fail forward.

The objective is not to design the perfect architecture on paper. It is to make progress, to reduce dependency, to regain control over costs and strategic direction, and to move to a platform that is predictable, supportable, and aligned with the organization’s own priorities. Even if it means it will stall innovation for a short time.

In that context, price becomes the first filter, not the final decision criterion.

If a platform is clearly unaffordable, the conversation ends there. But if the numbers are within reach, customers start to look deeper. They begin to evaluate operational simplicity, architectural consistency, support quality, and long-term flexibility.

That is usually the point where the Nutanix conversation truly starts.

The Perception Problem

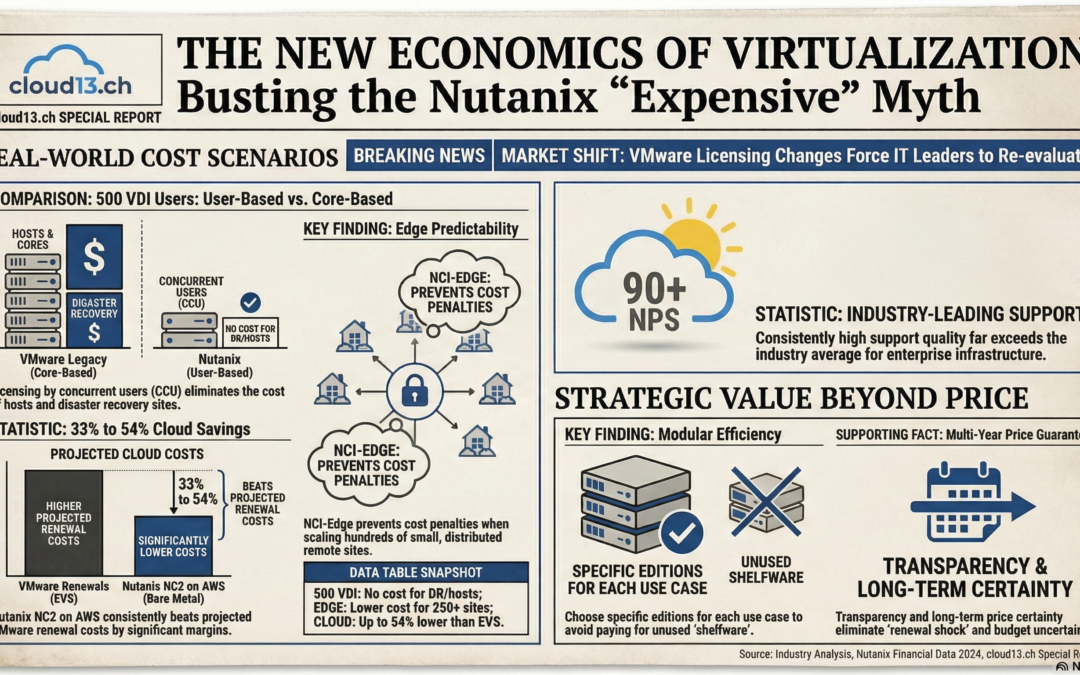

For years, a certain sentence has circulated in the market: “Nutanix is expensive”. It became one of those beliefs that many people repeat without necessarily remembering where it originally came from.

In some organizations, this perception is based on very old benchmarks. In others, it comes from comparisons where different functionality levels were evaluated against each other. And in some cases, it is simply a narrative that persisted over time.

Recently, I have revisited this perception through real customer scenarios. Not theoretical models, but practical environments with realistic configurations, conservative assumptions, and somtimes even with standard (pre-approved) discount levels. What I found was not a universal truth, but a context-dependent story.

In several scenarios, Nutanix was not only competitive but significantly cheaper.

Disclaimer: Before we look at the numbers, a short disclaimer is important. The scenarios shown here are based on realistic configurations, standard architectures, and pre-approved discount levels. They are meant to illustrate typical outcomes, not to serve as official quotes or universally applicable price promises. Actual pricing will always depend on the specific environment, commercial terms, hardware choices, and contractual conditions of each individual customer.

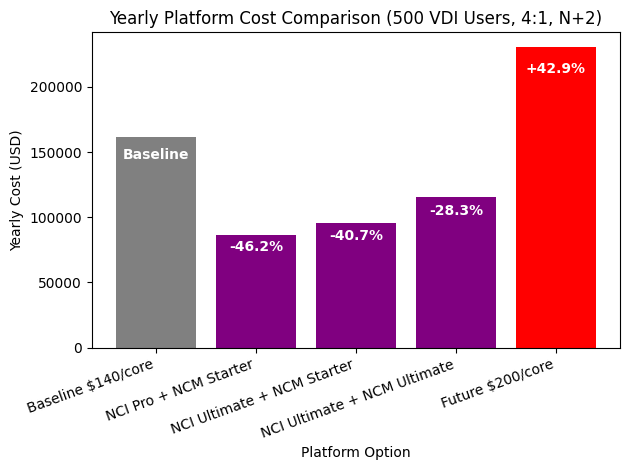

Scenario 1: 500 VDI Users

Assume a VDI environment with 500 users. The infrastructure is built on 2×32-core nodes and designed with an n+2 resilience model. This is a typical production setup, where spare capacity is included so that the environment can tolerate failures without affecting user sessions.

In this configuration, you end up with around 1’152 physical cores that need to be licensed at the platform level. For the baseline comparison, I used this number together with a price of $140 per core. This reflects a very common way the market still thinks about platform costs – total cores multiplied by a unit price. In this baseline, no disaster recovery site is included yet.

With Nutanix, I modeled the environment using the NCI-VDI edition, which is purpose-built for virtual desktop use cases with platforms like Citrix or Omnissa (or Parallels, Dizzion etc.). In this model, I am not licensing 1’152 cores. Instead, I am licensing 500 concurrent users (CCU).

The difference in licensing logic alone already changes the economics of the environment, but there is another aspect that often surprises customers.

There is no additional licensing cost for a disaster recovery site. You can add hosts, refresh hardware, or build a secondary VDI site with the same number of cores, and from a Nutanix licensing perspective, the price remains exactly the same. The licensing is tied to the number of concurrent users, not to the amount of infrastructure standing behind them.

To keep the scenario fully realistic, I calculated three Nutanix options using only pre-approved discounts. Meaning, these are price levels that can typically be offered without extraordinary approvals.

- The first option combined NCI Pro with NCM Starter – Representing a balanced configuration for standard VDI environments.

- The second option used NCI Ultimate with NCM Starter – For scenarios where additional capabilities such as microsegmentation are required.

- The third option was the full stack – Combining NCI Ultimate with NCM Ultimate, providing the complete feature set across both infrastructure and management layers.

All three options came out significantly below the core-based baseline, even the highest edition. And then there is the red bar in the comparison chart.

That red bar represents the same platform model as the baseline, but with the price per core increasing from $140 to $200, which is not an unrealistic assumption for a future renewal. The architecture stays the same, the number of cores stays the same, the resilience model stays the same, but only the unit price changes. Staying with the current platform vendor would result in a massive increase in total cost of ownership, without adding a single new capability to the environment.

This scenario is not meant to claim that Nutanix is always cheaper. That would be just another oversimplified narrative. But it does show that Nutanix can be more predictable, more scalable, and economically superior, especially in VDI environments where user-based licensing aligns better with how the platform is actually consumed.

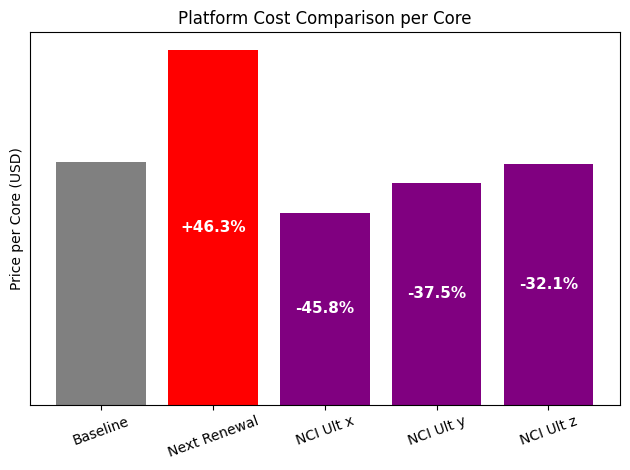

Scenario 2: Microsegmented Data Center

In another environment, the discussion was not about VDI or edge sites, but about security.

The customer had a clear, non-negotiable requirement. They wanted to limit lateral movement inside the network and enforce strict communication policies between workloads. This is becoming increasingly common, especially in regulated industries and public sector environments where zero-trust principles are becoming operational requirements.

In the past, microsegmentation was often tied to premium software bundles. Organizations that needed this capability had little choice but to move into higher-tier licensing models, even if they did not require many of the additional features included in those bundles. The security requirement effectively forced them into a more expensive edition, regardless of their actual needs.

In this scenario, the customer was already using microsegmentation and wanted to retain that capability in the target architecture. The comparison was therefore not between a basic and a premium edition, but between two functionally equivalent setups. Both sides had to include network security features.

To make the comparison more realistic and representative of different customer sizes, three Nutanix options were modeled. All three were based on the NCI Ultimate edition, which includes micro-segmentation capabilities, but they reflected different customer profiles and corresponding discount levels.

- The first option represented a large enterprise environment. In this case, the customer had a high core count and a larger overall deal size, which typically qualifies for higher discount tiers. This option assumed a larger-scale deployment and the kind of commercial conditions that are common in enterprise agreements. It illustrated how the platform behaves economically when deployed at a significant scale.

- The second option represented a mid-sized environment. Here, the core count and overall deal size were more moderate, leading to medium discount levels. This scenario is often closer to what many regional enterprises, healthcare providers, or mid-sized public sector organizations experience. It provided a balanced view between large enterprise conditions and smaller deployments.

- The third option reflected a smaller environment, with a lower core count and standard discount levels. This was designed to show what the platform looks like in more typical, smaller-scale deployments, where customers operate under normal commercial conditions without large enterprise agreements.

Across all three options, the architectural assumptions remained consistent. The same security requirements applied, the same functionality was included, and the comparison remained technically equivalent. The only real differences were the scale of the environment and the corresponding commercial terms.

In each of the three scenarios, the Nutanix configuration remained competitive, and in several cases came out lower in total software cost.

Scenario 3: Distributed Edge Environment

Instead of running a few large clusters in central data centers, some organizations suddenly find themselves operating dozens or even hundreds of small sites. Each location may only host a limited number of virtual machines (VMs), but the number of sites creates a very different licensing footprint.

In this scenario, the customer planned to run around 3’000 virtual machines distributed across roughly 250 edge locations. Each site consisted of only a small number of hosts, designed for local workloads and basic resilience – assume 3 hosts à 32 cores per site = 24’000 cores in total.

In traditional per-core licensing models, these kinds of distributed environments can become expensive very quickly. Even lightly utilized sites still require a certain number of cores to maintain resilience and availability. Multiply that by hundreds of locations, and the software cost grows faster than the actual workload.

Nutanix Cloud Infrastructure – Edge (NCI-Edge) provides a distributed infrastructure platform for small edge deployments. NCI-Edge provides the same capabilities as NCI, combining compute, storage, and networking resources from a cluster of servers into a single logical pool with integrated resiliency, security, performance, and simplified administration. NCI-Edge is limited to a maximum of 25 VMs in a cluster, with each VM being limited to a maximum of 96GB of memory. With NCI-Edge, organizations can efficiently extend the Nutanix platform to remote office/branch office (ROBO) and other edge use cases.

When we modeled this scenario with a Nutanix-based architecture, using conservative assumptions and standard pricing, the outcome was different. The total software cost across all 250 sites was lower than the comparable alternative.

Edge licensing is all about predictability. The licensing model aligned more closely with the operational reality of the environment. Instead of being penalized for running many small sites, the customer could scale their footprint without unexpected increases in costs. The economics made sense for a distributed architecture.

For organizations with large retail networks, industrial edge scenarios, transportation systems, or geographically spread infrastructures, this predictability can be just as important as the absolute price. It allows them to plan growth, roll out new sites, and standardize operations without constantly renegotiating their licensing model.

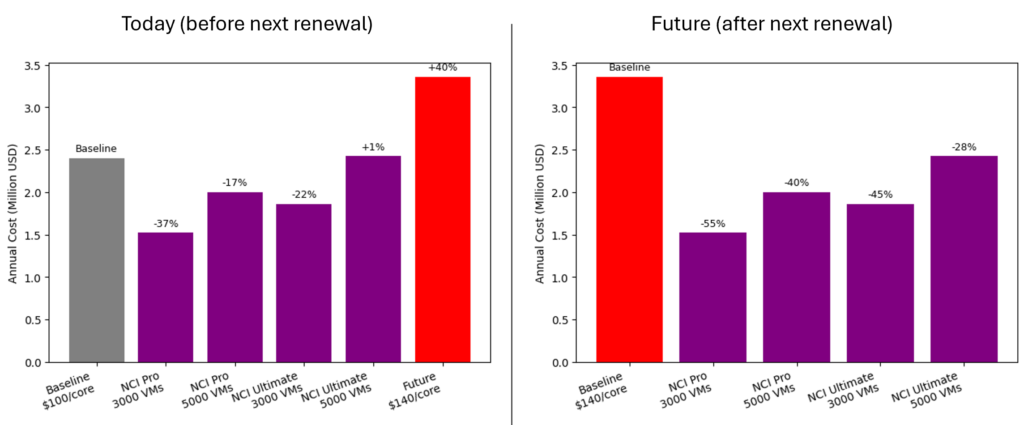

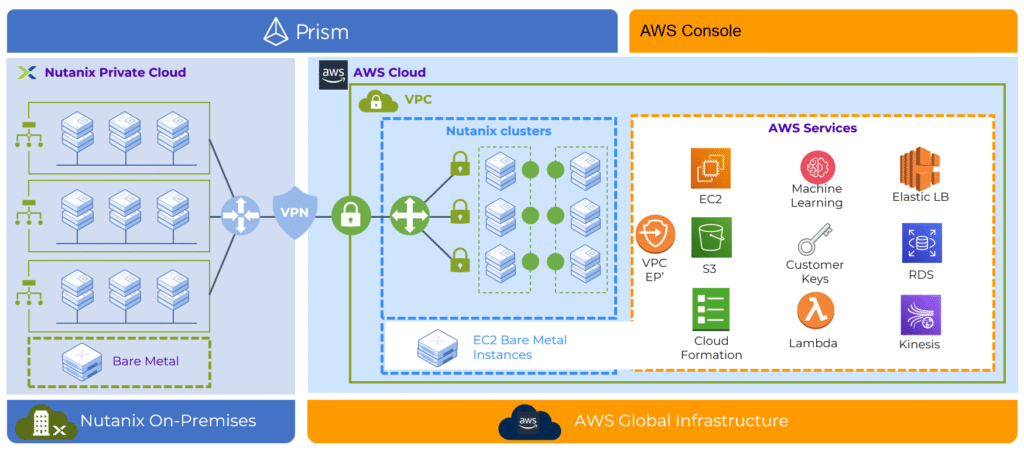

Scenario 4: From Amazon EVS to Nutanix NC2

Many organizations that moved, or are planning to move, to VMware environments in the public cloud have a very practical reason. They want to keep their existing operational model, their tools, and their skill sets, while shifting the physical infrastructure into a cloud provider’s (Azure, GCP, AWS) data center. The promise is always continuity without disruption.

At first glance, this approach makes sense. You avoid large migration projects, keep your processes intact, and simply relocate the environment. But the economics of these environments have started to change.

I am currently working with an organization that operates a full-stack private cloud at roughly $150 per core. On paper, that stack includes a wide range of capabilities. In reality, however, they only use a small portion of it: the core virtualization layer and basic monitoring and logging. No vSAN, no NSX. Just vSphere and Aria Operations.

Today, they run around 1’920 physical cores on-premises. As part of their cloud strategy, they are considering migrating to Amazon’s Elastic VMware Service (EVS) to exit their own data centers and align with a cloud-first approach. Because the EVS baremetal instances offer higher density, they expect to consolidate their environment to roughly 1’000 cores. Fewer cores, better utilization, same workloads.

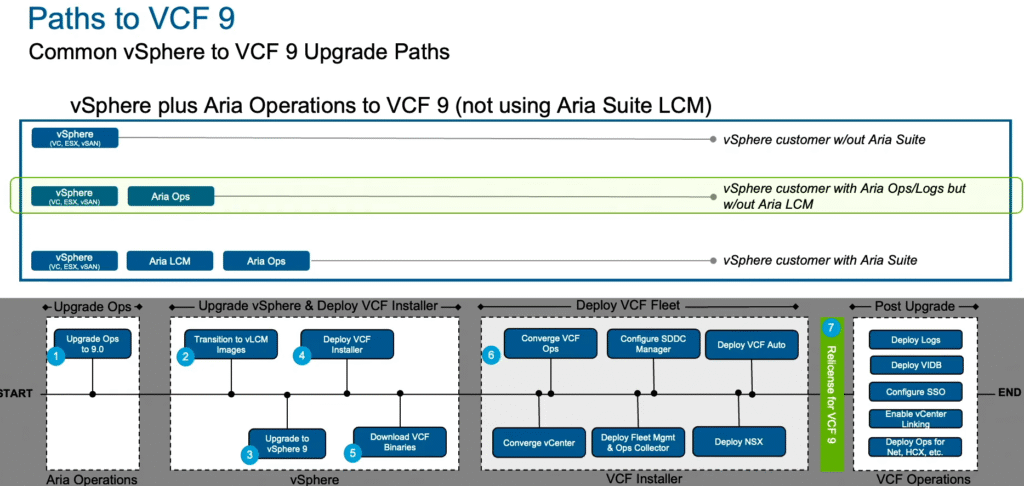

Because Amazon EVS is a self-managed service, you are responsible for the lifecycle management and maintenance of the VMware software used in the Amazon EVS environment, such as ESX, vSphere, vSAN, NSX, and SDDC Manager.

Note: Amazon EVS does not support VMware Cloud Foundation 9 at this time. Currently, the only supported VCF version is VCF 5.2.2 on i4i.metal instances.

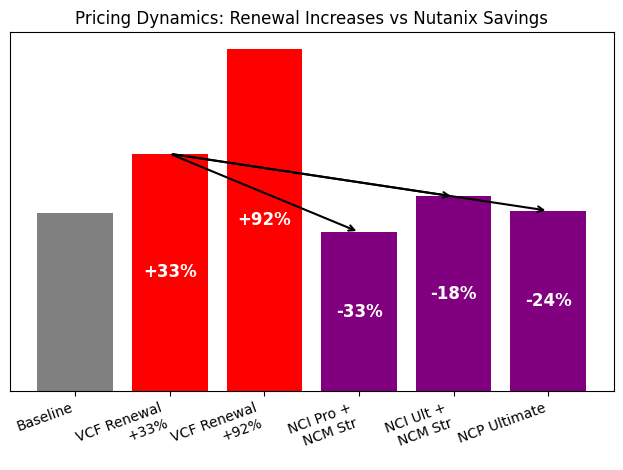

That sounds like a straightforward cost-saving exercise, right? But the renewal dynamics tell a different story. Their Broadcom renewal is scheduled for summer 2027, and two scenarios are being discussed:

- In the first scenario, a typical price increase of around 33 percent is assumed. That would move them from $150 to approximately $200 per core.

- In the second scenario, the total contract value remains the same despite the reduced core count. In practical terms, that would mean $288 per core, which means an increase of about 92% compared to today.

In other words, even if they cut their footprint almost in half, their effective price per core could nearly double. This is where the discussion turned toward alternatives.

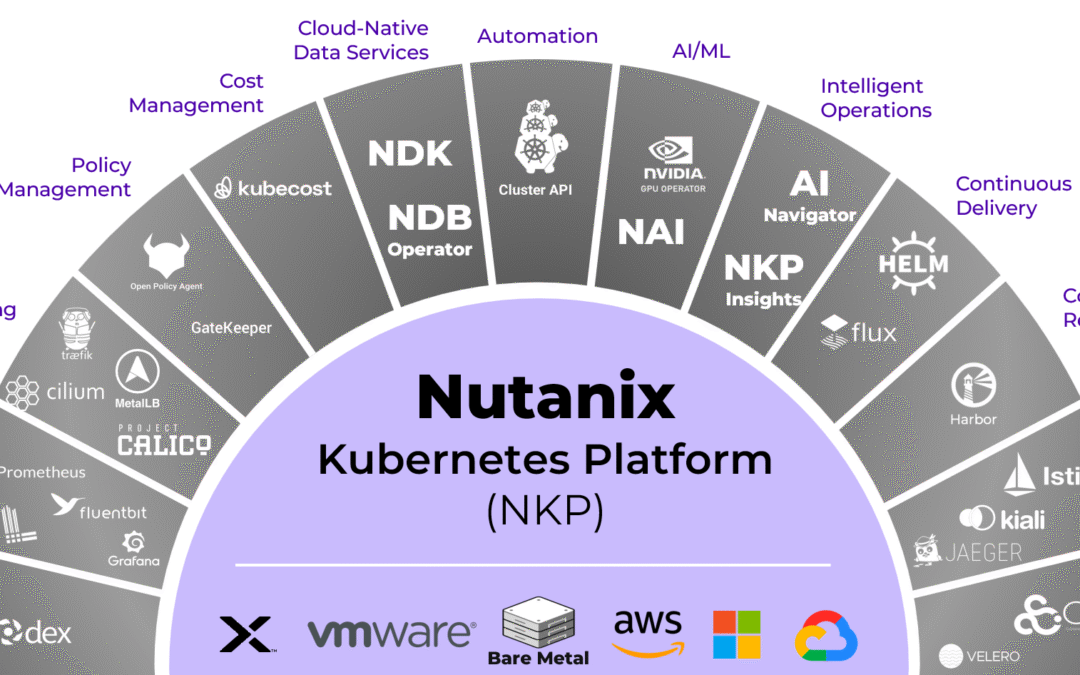

We modeled the same environment using the Nutanix Cloud Platform (NCP) running as NC2 on AWS. It is important to clarify one common misconception here: NC2 is not a separate product with a different architecture. It is the same Nutanix software stack, NCI combined with NCM, deployed on baremetal instances in the public cloud. Operationally, it behaves exactly like an on-premises Nutanix environment.

To reflect different functional needs, I modeled three options:

- The first option was NCI Pro combined with NCM Starter. This configuration mirrors the customer’s current feature usage, avoiding unnecessary capabilities or “shelfware”. It represents a like-for-like replacement of the existing functionality.

- The second option used NCI Ultimate with NCM Starter. This added more advanced storage and data services, along with microsegmentation capabilities, giving the customer a richer feature set than they have today.

- The third option was the full Nutanix Cloud Platform Ultimate stack, including the complete set of infrastructure, automation, and advanced platform services.

Even with these different configurations, the results were consistent. All three Nutanix options came in significantly below the expected VMware renewal costs.

Compared to a VMware renewal at $200 per core, the estimated savings looked roughly as follows:

-

NCI Pro + NCM Starter: About 33 percent lower

-

NCI Ultimate + NCM Starter: About 18 percent lower

-

NCP Ultimate: About 24 percent lower (higher discount for full-stack approach)

If the worst-case scenario of $288 per core were to materialize, the savings would be even higher, ranging from approximately 43 to 54 percent per year!

As in the other scenarios, the interesting part was not just the price difference. It was the combination of cost predictability and architectural flexibility. With NC2, the customer could run the same platform on-premises and in the cloud, move workloads between locations, and avoid being tied to a single proprietary cloud virtualization stack.

To support the transition from VMware to Nutanix on NC2, migrations are typically handled with Nutanix Move. This tool allows customers to replicate and migrate virtual machines from existing VMware environments into Nutanix clusters with minimal disruption, reducing the complexity of the platform shift.

In this scenario, the outcome once again challenged the old perception. When modeled with realistic assumptions and current pricing dynamics, Nutanix was very (cost-)competitive. It offered both a lower platform cost and a more flexible long-term architecture.

Scenario 5: Updated Benchmarks, Different Results

Perhaps one of the most revealing examples was not a technical scenario at all, but a simple conversation.

In one engagement, a partner mentioned that their internal Nutanix benchmark was more than two years old. Those numbers had shaped their perception of the platform and influenced how they positioned Nutanix in front of customers. Over time, the benchmark had become an accepted reference point, even though no one had revisited the assumptions underlying it.

When we recalculated the scenario using (VCF vs. NCI Pro with Advanced Replication add-on) current licensing models, realistic configurations, and today’s pricing structures, the outcome was very different from what they expected. The Nutanix solution turned out to be cheaper than expected.

The important information here was not the percentage difference or the exact numbers on the spreadsheet. It was the realization that the entire perception had been built on outdated data. The conclusion they had carried forward for years no longer reflected the reality of the current market.

This experience is not unique. Many organizations still rely on benchmarks, cost models, or architectural assumptions that were created several years ago. Since then, licensing structures have evolved, bundles have changed, and the economics of different platforms have shifted. But the original perception often remains untouched.

In conversations with customers and partners, I frequently hear a similar sentence: “Our Nutanix benchmark might be outdated”. That simple realization often marks the turning point in the discussion. Because once the numbers are recalculated with current data, the story tends to change and the outcome is no longer predetermined.

Addressing the Renewal Myth

Another concern that often surfaces in conversations is the idea that Nutanix offers an attractive entry price, only to significantly increase costs at renewal time.

This narrative circulates in online forums, informal discussions, and peer-to-peer exchanges. In a market where many organizations have recently experienced unexpected price increases from other vendors, it is understandable that customers approach any new platform with a certain level of skepticism. Trust in licensing models has been shaken, and nobody wants to repeat the same experience a few years down the road.

But in practice, this perception does not reflect how most Nutanix engagements actually unfold. In many cases, Nutanix is able to provide multi-year price guarantees, giving customers clarity not only about the initial investment, but also about what they can expect over the next several years. Instead of treating pricing as a short-term negotiation, the conversation often shifts toward long-term planning and predictability.

This does not mean that prices will remain frozen forever. No software vendor can realistically promise that. Over time, platforms evolve, new features are introduced, innovation continues, and inflation affects the cost structure. It is normal for software pricing to adjust over a multi-year horizon.

The difference lies in transparency.

Rather than hiding future changes behind complex contracts or vague terms, Nutanix is often willing to put the long-term numbers on the table early in the process. Customers can see not only what they pay today, but also how the platform is expected to evolve financially over time. That creates a different kind of conversation – one based on planning and predictability instead of uncertainty.

For many organizations, especially those in regulated industries or the public sector, that predictability is more important than the absolute entry price. It allows them to align budgets, procurement cycles, and strategic roadmaps without the fear of sudden surprises at renewal time.

What Customers Actually Value

Once the initial price discussion is out of the way, the tone of the conversation usually changes. The focus shifts from raw numbers to what the platform actually delivers in day-to-day operations.

At this stage, customers are asking whether it fits their architecture, their processes, and their long-term strategy. And across many conversations, certain themes tend to appear again and again.

One of the most frequently mentioned aspects is the modularity of the platform. Customers appreciate that Nutanix does not force them into a single, monolithic bundle for every use case. A large data center, a VDI environment, and a small edge site may not require the same software edition. With Nutanix, these environments can be licensed differently based on their actual requirements. This flexibility allows customers to align their licensing model with their architecture, instead of reshaping their architecture to fit the licensing.

Another recurring theme is the architectural simplicity of hyperconverged infrastructure itself. Many customers value a distributed system that integrates compute and storage, builds resilience into the platform, and reduces external dependencies. There is no separate SAN to manage, no complex compatibility matrix between multiple storage and compute components. For teams that want to reduce operational overhead and complexity, this design principle often resonates more strongly than any individual feature.

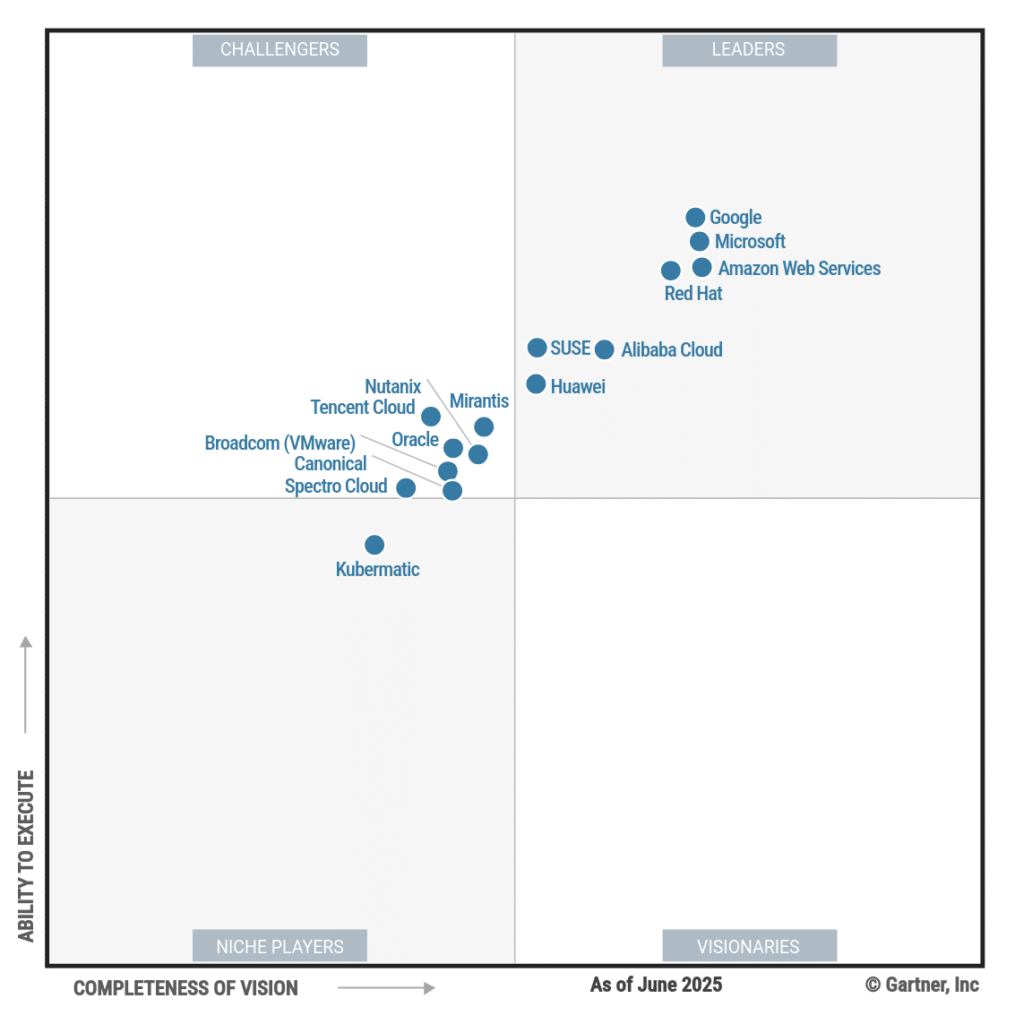

Support quality is another topic that comes up regularly. Nutanix consistently achieves a Net Promoter Score (NPS) above 90, which is unusually high in the enterprise infrastructure space. Customers often describe the support experience as direct and focused, with engineers who stay engaged until the issue is resolved. For organizations that have struggled with multi-vendor support models in the past, this can be a significant improvement.

The ecosystem also plays an important role. Nutanix continues to work closely with major OEM partners such as Dell, Lenovo, HPE, and Cisco. For many customers, especially in the public sector, this is more than a technical detail. It means they can procure hardware through existing framework contracts, trusted suppliers, and established procurement channels, while still running a modern, consistent software platform.

In addition, the platform is gradually opening up to more flexible architectures. Nutanix has introduced support for external storage integrations, starting with platforms from Dell and Pure Storage, with further options expected over time. This gives customers more freedom in how they design their environments, especially if they want to reuse existing storage investments or follow a disaggregated approach for certain workloads.

Taken together, these themes paint a clear picture. Once the price question is answered, the decision is rarely about a single feature or a benchmark number. It becomes a broader evaluation of architecture, operational simplicity, support experience, and long-term flexibility.

And in many of those discussions, that combination of qualities is what makes the platform stand out.

Price Opens the Door. Value Closes the Deal.

If you look across all the scenarios and customer discussions, a consistent pattern begins to emerge.

Price is almost always the starting point. It determines whether a platform even makes it onto the shortlist. In today’s market, where many organizations are under pressure to control costs and justify every investment, that first filter has become more important than ever. If a solution is clearly out of budget, the conversation usually ends before it truly begins.

But we all know that price is rarely the final decision factor.

Once customers see that Nutanix is within their financial reach, or in some cases even cheaper than the alternatives, the focus shifts. The discussion shifts from license metrics and discount levels to the day-to-day realities of running the platform. This is the moment when the conversation moves from procurement to platform strategy.

Customers begin to consider how much time they spend on upgrades, how complex their current environment has become, how many vendors they have to coordinate during incidents, and how predictable their infrastructure roadmap really is. They start to evaluate not just what the platform costs today, but what it means for their operations over the next five or ten years.

And that is often where Nutanix stands out!

The platform may not always be the absolute cheapest option in every possible scenario. No serious technology decision should be based on a single number alone. But the blanket statement that Nutanix is inherently expensive does not hold up when you look at real environments with current data.