10 Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Nutanix

Nutanix is often described with a single word: HCI. That description is not wrong, but it is incomplete.

Over the last decade, Nutanix has evolved from a hyperconverged infrastructure (HCI) pioneer into a mature enterprise cloud platform that now sits at the center of many VMware replacement strategies, sovereign cloud designs, and edge architectures. Yet much of this evolution remains poorly understood, partly because old perceptions persist longer than technical reality.

Here are ten things about Nutanix that people often don’t know or underestimate.

1. Nutanix’s DNA is HCI, but the architecture has evolved beyond it

Nutanix was built on hyperconverged infrastructure. That heritage is important, because it shaped the platform’s operational model, automation mindset, and lifecycle discipline.

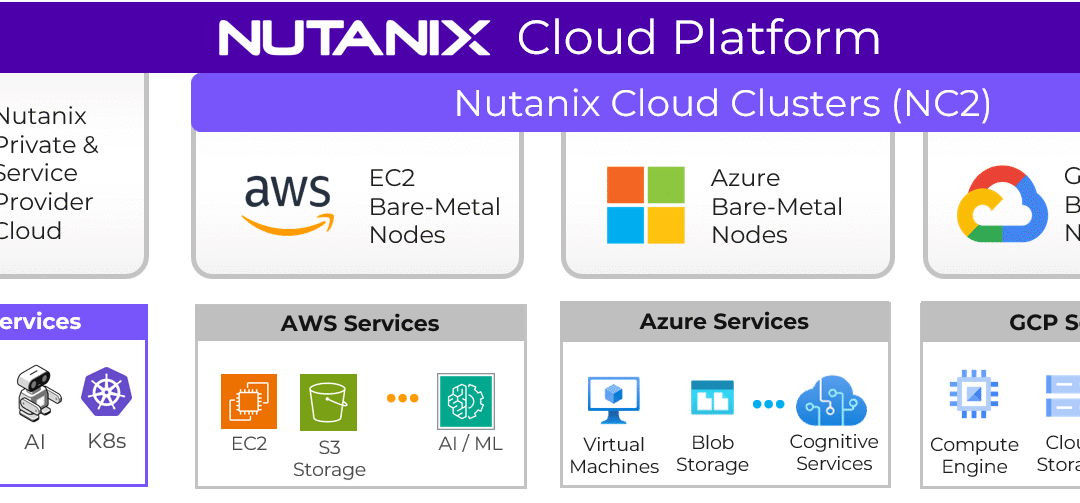

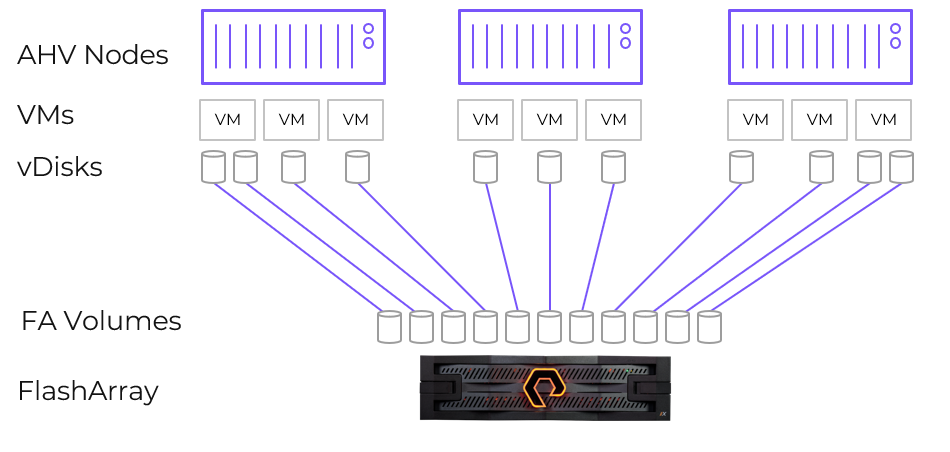

Over the last years, Nutanix deliberately opened its architecture. Today, compute-only nodes are a possibility, enabled through partnerships with vendors like Dell (PowerStore support for Nutanix is expected to enter early access in spring 2026, with general availability coming in summer 2026) and Pure Storage (for now). This allows customers to decouple compute and storage where it makes architectural or economic sense, without abandoning the Nutanix control plane.

This is Nutanix acknowledging that real enterprise environments are heterogeneous, and that flexibility matters.

2. A Net Promoter Score above 90

Nutanix has reported an NPS score consistently above 90 for several years. In enterprise infrastructure, that number is almost unheard of.

NPS reflects how customers feel after deployment, during operations, upgrades, incidents, and daily use. In a market where infrastructure vendors are often tolerated rather than liked, this level of advocacy is just unique and tells a story if its own.

It suggests that Nutanix’s real differentiation is not just technology, but operational experience. That tends to show up only once systems are running at scale.

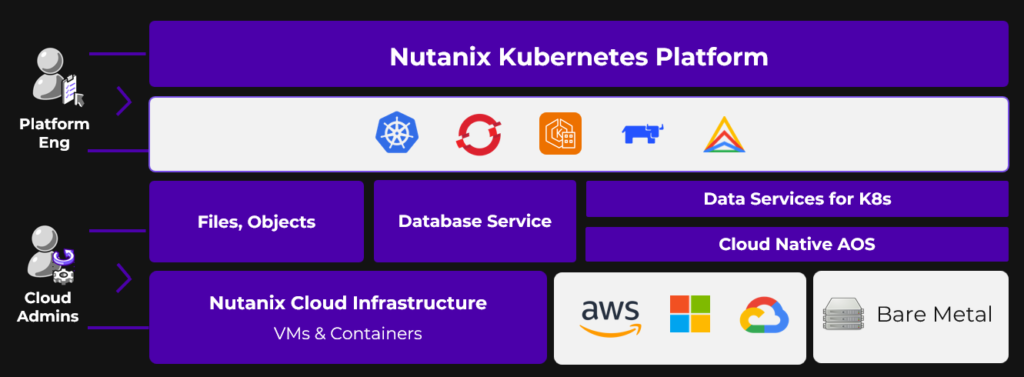

3. Nutanix Kubernetes Platform runs almost everywhere

Nutanix Kubernetes Platform (NKP) is often misunderstood as “Kubernetes on Nutanix”. That is only partially true.

NKP can run on:

- Bare metal

- Nutanix AHV

- VMware

- Public cloud infrastructure

NKP was designed to abstract infrastructure differences rather than enforce platform lock-in. For organizations that already operate mixed environments, or that want to transition gradually, this matters far more than ideological purity.

In practice, NKP becomes a control layer for Kubernetes. That is especially relevant in regulated or sovereign environments where infrastructure choices are often political as much as technical.

4. Nutanix has matured from “challenger” to enterprise-grade platform

It’s honest to acknowledge that Nutanix wasn’t always considered enterprise-ready. In its early years, the company was widely admired for innovation and simplicity, but many large organizations hesitated because the platform, like all young software, had feature gaps, stability concerns in some use cases, and a smaller track record with mission-critical workloads.

That landscape has changed significantly. Over the past several years, Nutanix has steadily strengthened every axis of its platform. From virtualization and distributed storage to Kubernetes, security, and operations at scale. The company’s most recent financial results show that this maturity isn’t theoretical. Fiscal 2025 delivered 18 % year-over-year revenue growth, strong recurring revenue expansion, and Nutanix added thousands of new customers, including over 50 Global 2000 accounts, arguably its strongest annual new-logo performance in years.

What this means in practice is that many enterprises that once saw Nutanix as a “challenger” now see it as a credible and proven alternative to VMware, and not just in smaller or departmental deployments, but across core data center and hybrid cloud estates.

The old maturity gap has largely disappeared. What remains is a difference of philosophy. Nutanix prioritizes operational simplicity, flexibility, and choice, without compromising the robustness that large organizations demand. And with increasing adoption among Global 2000 enterprises, that philosophy is proving not only viable but competitive at the highest levels of IT decision-making.

5. The “Nutanix is expensive” perception is outdated and often wrong

The idea that Nutanix is more expensive than competitors is one of the most persistent myths in the market. It was shaped by early licensing models and by superficial price comparisons that ignored operational and architectural differences.

Today, Nutanix offers multiple licensing models, including options that other vendors simply do not have.

For example, NCI-VDI for Citrix or Omnissa environments is licensed based on concurrent users (CCU) rather than physical CPU cores. That aligns cost directly with usage and not hardware density.

Even more interesting is NCI Edge, which is designed for distributed environments with smaller footprints (aka ROBO). It is licensed per virtual machine, with clear boundaries:

- Maximum of 25 VMs per cluster

- Maximum 96 GB RAM per VM

Consider a realistic example. An organization runs 250 edge sites. Each site has a 3-node cluster with 32 cores per node and hosts 20 VMs:

- A core-based model would require licensing 24’000 cores

- With NCI Edge, the customer licenses 5’000 VMs

It fundamentally changes the cost structure of edge and remote deployments. In a traditional core-based licensing model, effective costs might range from $100 to $140 per core for edge nodes. With NCI Edge, the effective per-core cost can drop to $60-80 (illustrative figures). This is not a marginal optimization, it’s huge.

Note: NCM Edge is a product that provides the same capabilities as NCM for edge use cases. NCM-Edge is also limited to a maximum of 25 VMs in a cluster.

6. Almost 90% of Nutanix customers now use AHV

Nutanix has always been fundamentally about HCI and AOS (Acropolis Operating System). From the beginning, the value was never the hypervisor itself, but the distributed storage, data services, and operational model built on top of it. Over time, Nutanix came to a clear conclusion: The hypervisor should be a commodity, not the value anchor of the platform. Out of this thinking, the perception, and later the expression, emerged that AHV is “free”.

Today, AHV has become the dominant deployment model in the Nutanix ecosystem, with an adoption rate of 88%. This matters for two important reasons. First, it disproves the assumption that customers need to be pushed or incentivized to move to AHV. Second, it demonstrates that AHV is trusted to run mission-critical workloads at scale, across enterprises and service providers.

7. Nutanix is 100% channel-led

Nutanix does not sell directly to customers (for sure there are some exceptions :)). It is a channel-led vendor, by design, and that decision fundamentally shapes how the company operates in the market. Hence, channel commitment at Nutanix is a structural principle.

Partners are not treated as a fulfillment layer or a transactional necessity. They are core to how Nutanix delivers value – from architecture design and implementation to day-two operations, managed services, and long-term customer success. As a result, Nutanix has built one of the strongest partner and service provider ecosystems in the industry, with clear incentives, predictable rules, and room for partners to build sustainable businesses.

This stands in sharp contrast to the current direction of some other infrastructure vendors, where channel models have become more restrictive, less transparent, and increasingly centered around direct control. In that environment, partners often struggle with margin pressure, reduced influence, and uncertainty about their long-term role.

Nutanix takes a different approach. By staying channel-led, it enables local expertise, regional sovereignty, and trusted delivery models, which are especially critical in public sector, regulated industries, and markets where locality and compliance matter as much as technology.

8. MST and Cloud-Native AOS show how far Nutanix has moved beyond classic HCI

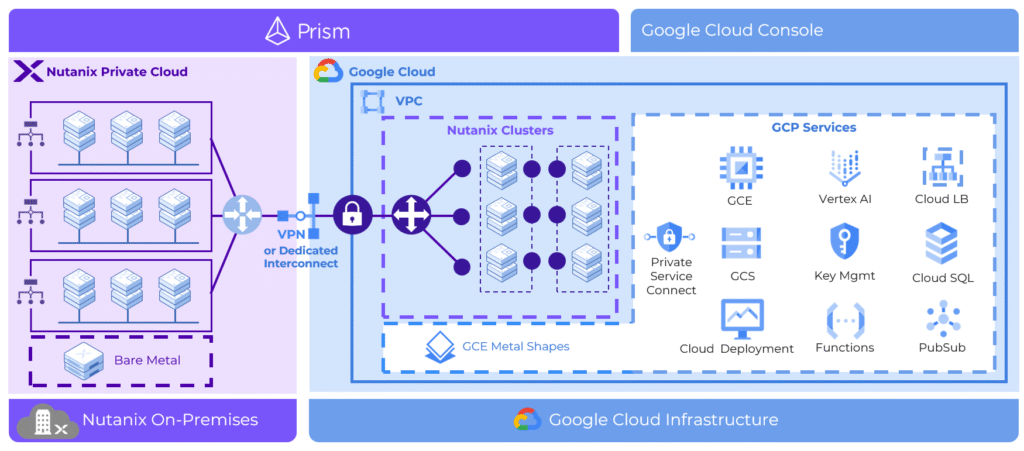

Most people associate Nutanix AOS with hyperconverged infrastructure and VM-centric deployments. What is far less known is how deeply Nutanix has evolved its data platform to address multi-cloud and cloud-native architectures.

One example is MST (Multi-Cloud Snapshot Technology). MST enables application-consistent snapshots to be replicated across heterogeneous environments, including on-premises infrastructure and public clouds. Unlike traditional disaster-recovery approaches that assume identical infrastructure on both sides, MST is designed for asymmetric, real-world scenarios. This makes it possible to use the public cloud as a recovery or failover target without re-architecting workloads or maintaining a second, identical private environment.

In parallel, Nutanix has introduced Cloud Native AOS, which brings enterprise-grade storage and data services directly into Kubernetes environments. Instead of tying storage to virtual machines or specific infrastructure stacks, Cloud Native AOS runs as a Kubernetes-native service and can operate across diverse platforms. This allows stateful applications to benefit from Nutanix data services, such as snapshots, replication, and resilience, without forcing teams back into VM-centric models.

Together, MST and Cloud-Native AOS illustrate an important point. Nutanix is not simply extending HCI into new form factors. It is re-architecting core data services to work across clouds, infrastructures, and application models. These capabilities are often overlooked, but they are strong indicators of where the platform is heading — toward data mobility, resilience, and consistency across increasingly fragmented environments.

9. Nutanix SaaS without forcing SaaS

Nutanix offers SaaS-based services such as Data Lens and Nutanix Central. These services are also available on-premises, including for air-gapped environments.

This dual-delivery model recognizes that not all customers can or should consume control planes as public SaaS.

10. Nutanix has more than a decade of real-world experience replacing VMware

Nutanix has operated alongside VMware for more than ten years, in many cases within the same environments. As a result, replacing vSphere is not a new ambition or a reactive strategy for Nutanix. It is just a long-standing and proven reality.

Equally important is the migration experience. Nutanix Move was built specifically to address one of the most critical challenges in any platform transition. It’s about getting workloads across safely, predictably, and at scale. Move supports migrations from vSphere, Hyper-V, AWS, and other environments, enabling phased and low-risk transitions rather than disruptive “big bang” projects. Beyond workload migration, Move can also translate NSX network and security policies into Nutanix Flow, addressing one of the most commonly cited blockers in VMware exit strategies.

Nutanix has spent more than a decade refining these aspects across thousands of customer environments, which is why many organizations today view it as a credible, de-risked alternative for the long term.

Conclusion

For organizations reassessing their infrastructure strategy, whether driven by VMware uncertainty, edge expansion, regulatory pressure, or cloud cost realities, Nutanix should be on the top of your list. It is a proven platform with a clear philosophy, a growing enterprise footprint, and more than a decade of hard-earned experience. If Nutanix is still on your shortlist as “HCI”, it may be time to look again, and this time at the full picture! 🙂