The New Rationality of Digital Sovereignty

For decades, digital transformation followed a clear logic. Efficiency, scale, and innovation were the ultimate measures of progress. Cloud computing, global supply chains, and open ecosystems seemed to be the rational path forward. The idea of “digital sovereignty”, meaning the control over one’s digital infrastructure, data, and technologies, was often viewed as a political or bureaucratic concern, something secondary to innovation and growth.

But rationality itself is not static. What we perceive as “reasonable” depends on how we define utility and risk. The Expected Utility Theory from behavioral economics tells us that every decision under uncertainty is guided not by objective outcomes, but by how we value those outcomes and how we fear their alternatives.

If that’s true, then digital sovereignty is not only a political mood swing, but also a recalibration of what societies see as valuable in an age where uncertainty has become the dominant variable.

Expected Utility Theory – Rationality Under Uncertainty

When we speak about rationality, we often assume that it means making the “best” choice. But what defines best depends on how we perceive outcomes and risks. The Expected Utility Theory (EUT), first introduced by Daniel Bernoulli and later refined by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, offers a framework to understand this.

EUT assumes that rational actors make decisions by comparing the expected utility of different options, not their absolute outcomes. Each possible outcome is weighted by the likelihood of its occurrence and the subjective value, or utility, assigned to it.

In essence, people don’t choose what’s objectively optimal. They choose what feels most secure and beneficial, given how they perceive risk.

What makes this theory profound is that utility is subjective. Humans and institutions value losses and gains asymmetrically. Losing control feels more painful than gaining efficiency feels rewarding. As a result, decisions that appear “irrational” in economic terms can be deeply rational when viewed through the lens of stability and trust.

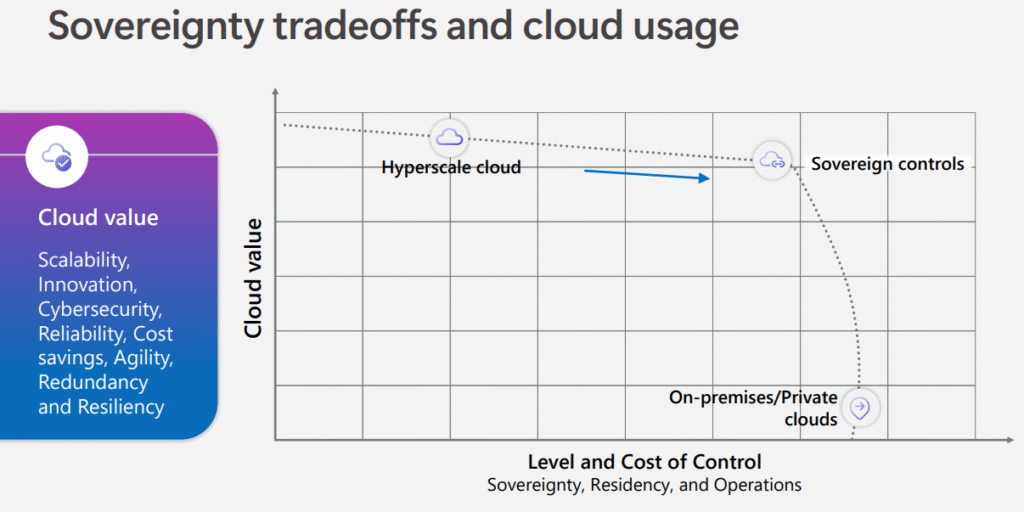

In a world of increasing uncertainty – geopolitical, technological, and environmental – the weighting in this equation changes. The expected cost of dependency grows, even if the actual probability of disruption remains small. Rational actors adjust by rebalancing their notion of utility. They begin to value autonomy, resilience, and continuity more than convenience.

In this sense, EUT doesn’t just describe individual behavior. It reflects the collective psychology of societies adapting to systemic uncertainty by explaining why the pursuit of digital sovereignty is not driven by emotion, but by a rational redefinition of what it means to be safe, independent, and future-ready.

Redefining Utility in a Fragmented World

The Expected Utility Theory states that rational actors make choices based on expected outcomes, the weighted balance of benefits and risks. Yet these weights are subjective. They shift with context, history, and collective experience.

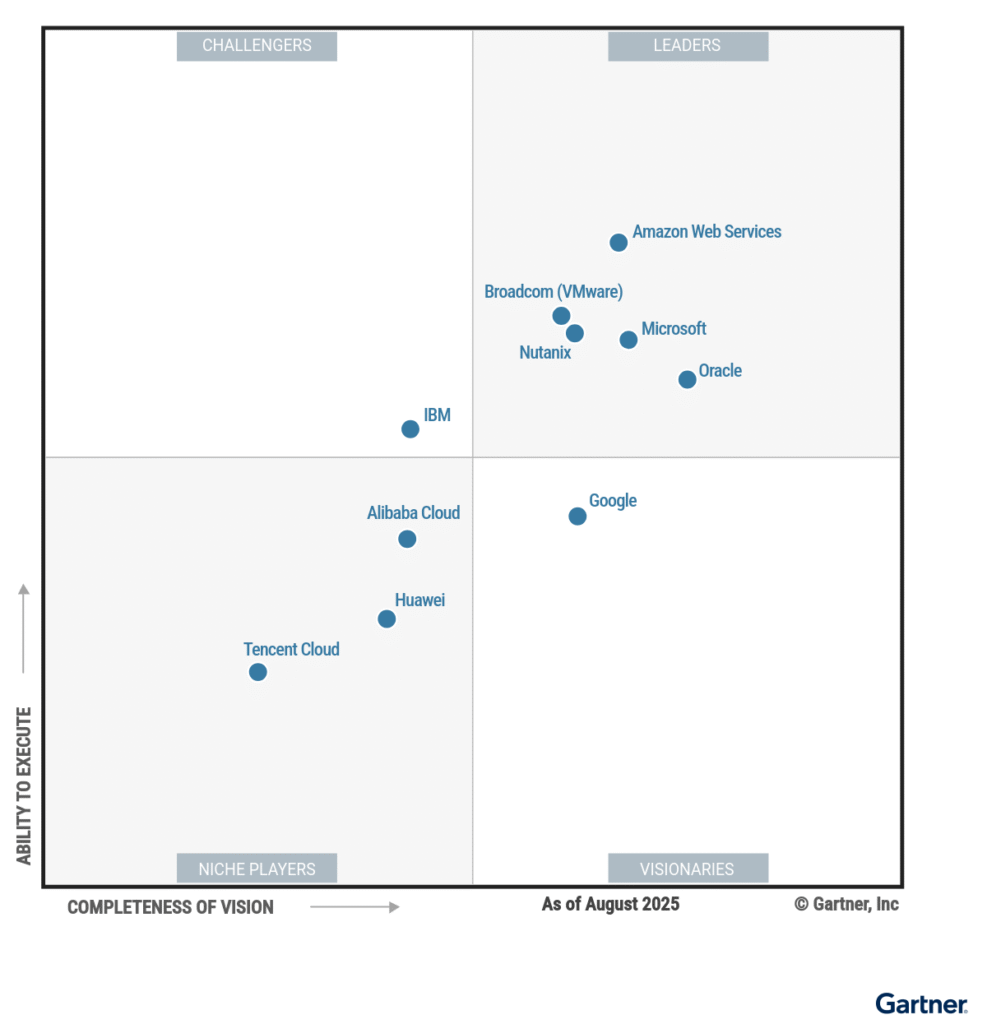

In the early cloud era, societies assigned high utility to efficiency and innovation, while the perceived probability of geopolitical or technological disruption was low. The rational choice, under that model, was integration and interdependence.

Today, the probabilities have changed, or rather, our perception of them. The likelihood of systemic disruption, cascading failures across tightly connected digital and geopolitical systems, no longer feels distant. From chip shortages to data jurisdiction disputes and the limited transparency of AI models, the cost of dependency has become part of the rational calculus.

Sovereignty as Expected Utility

What we call “digital sovereignty” is, at its core, a decision under uncertainty. It asks: Who controls the systems that control us? And what happens if that control shifts?

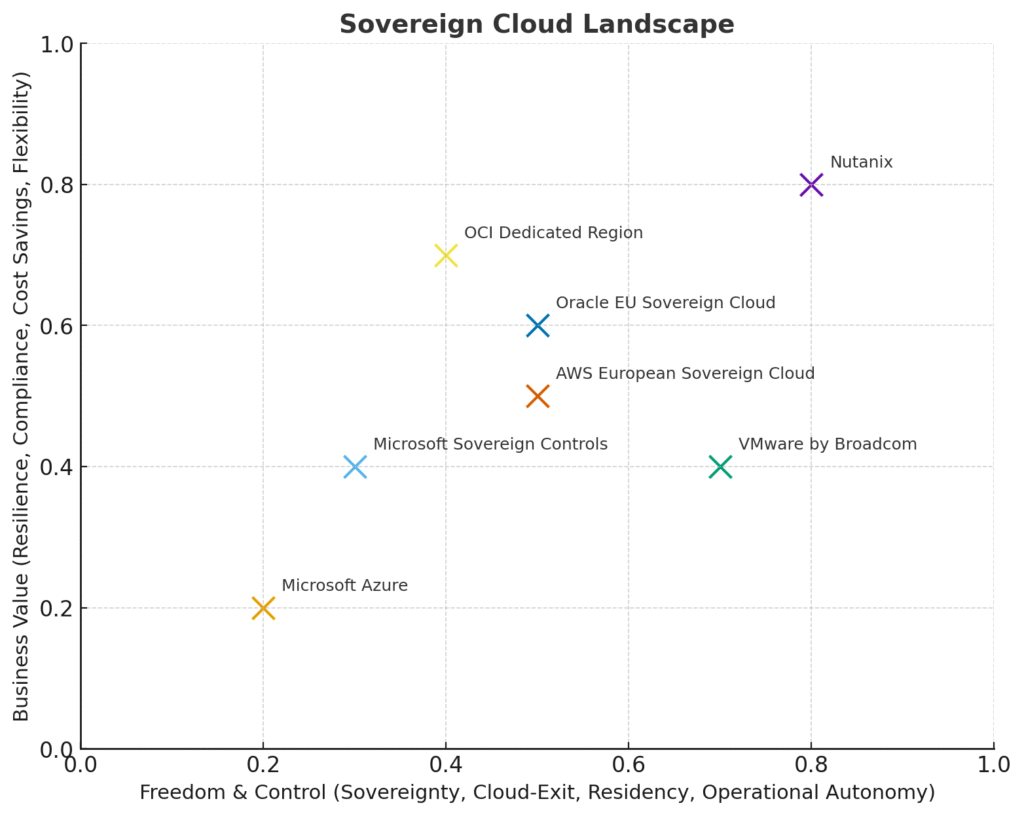

When the expected utility of autonomy exceeds the expected utility of convenience, societies change course. This is precisely what we are witnessing now. A collective behavioral shift in which resilience, trust, and control carry more weight than frictionless innovation.

Consider the examples:

-

Geopolitics has made technological dependence visible as a strategic vulnerability

-

Cybersecurity incidents have revealed that data sovereignty equals national security

-

AI and cloud governance have shown that control over infrastructure is also control over narrative and the flow of knowledge

Under these pressures, sovereignty is no longer a romantic ideal. It becomes a rational equilibrium point. The point at which perceived risks of dependency outweigh the marginal gains of openness.

From Emotional to Rational Sovereignty

In the past, sovereignty was often treated as nostalgia. A desire for control in a world that had already moved beyond borders. But what if this new form of sovereignty is not regression, but evolution?

Expected Utility Theory reminds us that rational behavior adapts to new distributions of risk. The same actor who once outsourced infrastructure to gain efficiency might now internalize it to regain predictability. The logic hasn’t changed, but the world around it has.

This means that digital sovereignty is not anti-globalization. It is post-globalization. It recognizes that autonomy is not isolation, but a condition for meaningful participation.

Autonomy as the Foundation of Participation

To participate freely, one must first possess the ability to choose. That is the essence of autonomy. It ensures that participation remains voluntary, ethical, and sustainable. Autonomy allows a nation to cooperate globally while retaining control over its data and infrastructure. It allows a company to use shared platforms without surrendering governance. It allows citizens to engage digitally without becoming subjects of invisible systems.

In this sense, autonomy creates the conditions for trust. Without it, participation turns into a relationship defined by dependence rather than exchange.

Post-globalization, therefore, represents not the end of the global era, but its maturation. It transforms globalization from a process of unchecked integration into one of mutual sovereignty: A world still connected, but built on the principle that every participant retains the right and capability to stand independently.

Sovereignty, in this light, becomes the structural balance between openness and ownership. It is what allows a society, an enterprise, or even an individual to remain part of the global system without being consumed by it.

The Return of Control as Rational Choice

Post-globalization has taught us that the strength of a system no longer lies in how open it is, but in how consciously it manages its connections. The same logic now applies to the digital realm.

Societies are learning to calibrate openness with control. They are rediscovering that stability and agency are not obstacles to innovation, but its foundation.

Expected Utility Theory helps make this visible. As uncertainty rises, the perceived utility of autonomy grows. What once appeared as overcaution now reads as wisdom. What once seemed like costly redundancy now feels like strategic resilience.

Control, long misunderstood as inefficiency, has become a new form of intelligence. It is a way to remain adaptive without becoming dependent. Sovereignty, once framed as resistance, now stands for continuity in an unstable world.

The digital age no longer rewards blind efficiency. It rewards balance, which is the ability to stay independent when the systems around us begin to drift.