Cloud-Konzentrationsrisiko beim Bund – Vielfalt oder nur Scheinvielfalt?

Hinweis: Dieser Beitrag spiegelt ausschliesslich meine persönliche Meinung und Einschätzung wider. Er basiert auf öffentlich zugänglichen Informationen sowie eigenen Analysen und Erfahrungen. Er stellt nicht die offizielle Position oder Meinung meines Arbeitgebers dar.

In meinem vorherigen Artikel zur Swiss Government Cloud (SGC) habe ich beleuchtet, welche Risiken entstehen, wenn man während der Migration alter Anwendungen zu lange mit der eigentlichen Modernisierung wartet. Heute möchte ich auf einen anderen, eng damit verbundenen Aspekt eingehen: die Frage, ob die beim Bund offiziell propagierte Vielfalt an Cloudanbietern in der Praxis tatsächlich existiert oder ob wir es am Ende nur mit einer Scheinvielfalt zu tun haben.

Vielfalt in der Theorie und die Vorgaben von WTO20007

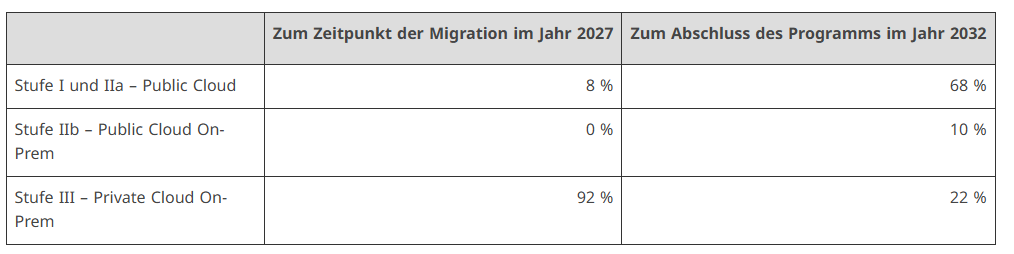

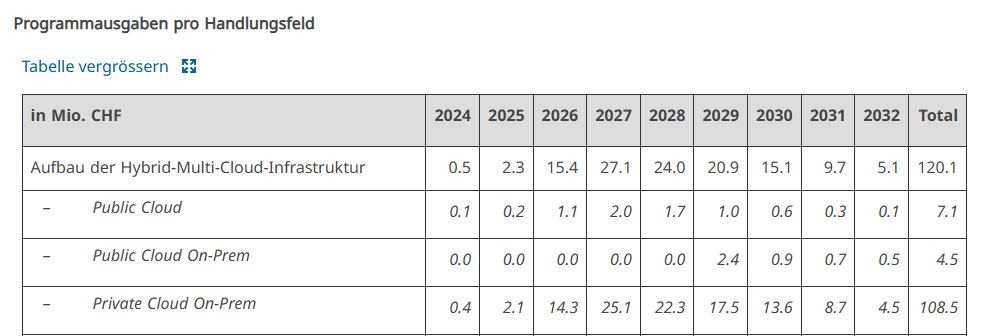

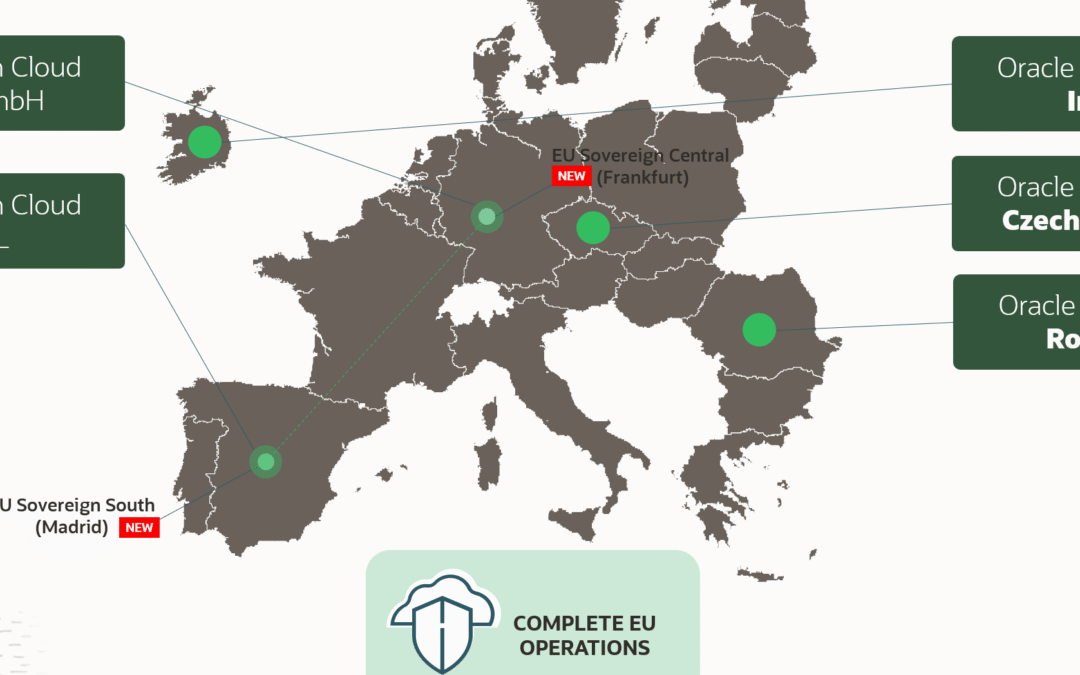

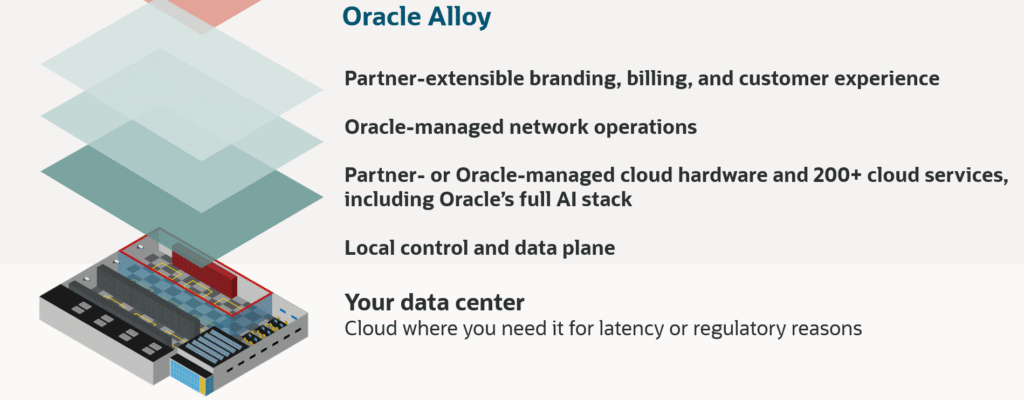

Seit der Ausschreibung WTO20007 hat die Bundesverwaltung formal Zugriff auf die Public-Cloud-Leistungen von fünf grossen Anbietern: Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, Oracle, IBM und Alibaba Cloud. Ergänzt wird das durch die Private-Cloud-Infrastruktur des BIT, die primär auf VMware-Technologien basiert.

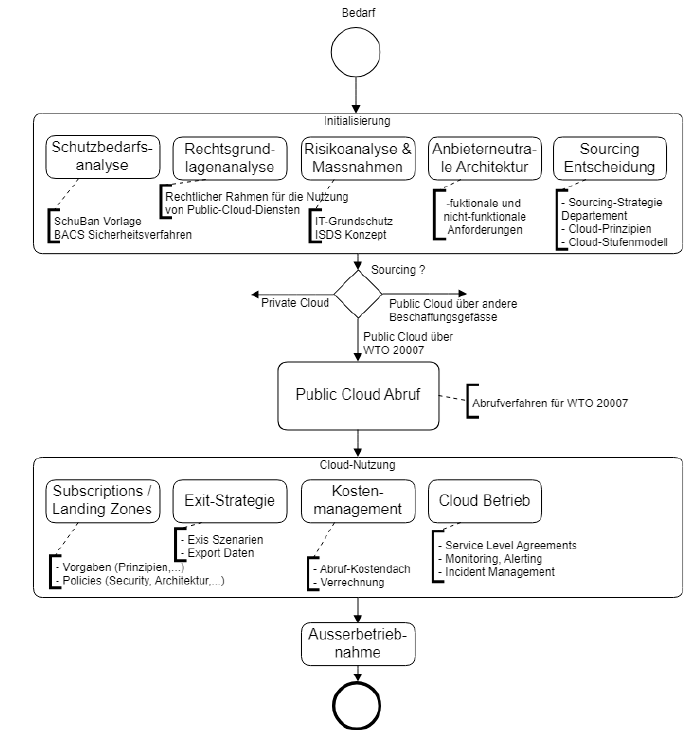

Die Theorie klingt ideal: Leistungsbezüger sollen aus einem breiten Spektrum von Cloudanbietern auswählen können, um für jede Anwendung die beste Plattform zu finden. Dafür existiert ein definierter Abrufprozess, der mit einem anbieterneutralen Pflichtenheft beginnt.

Dieses Pflichtenheft beschreibt die funktionalen, technischen und sicherheitsrelevanten Anforderungen der geplanten Anwendung. Dazu gehört ein Kriterienkatalog, der vorgibt, wie die Anbieterangebote bewertet werden. Basierend darauf erstellt ein Angebotsteam für alle fünf Public-Cloud-Anbieter passende Konfigurationen unter Verwendung der Preisinformationen für die jeweils gültige Region.

Falls ein Anbieter ein oder mehrere Ausschlusskriterien nicht erfüllt, wird dies dokumentiert. Am Ende liegen maximal fünf Konfigurationen vor, die im Evaluationsbericht objektiv miteinander verglichen werden. Ja, ganz nach den Regeln des Pflichtenhefts. Der Bericht hält den Ablauf fest und begründet den finalen Abrufentscheid.

In dieser strukturierten, formal sauberen Welt könnte man annehmen: Vielfalt ist garantiert.

Das Konzentrationsrisiko

Auf dem Papier klingt eine breite Streuung auf viele Cloudanbieter wie eine Risikoreduzierung, aber in der Praxis kann es jedoch genau das Gegenteil bewirken.

Jeder zusätzliche Anbieter bedeutet einen weiteren Technologie-Stack, eigene Schnittstellen, Sicherheitsrichtlinien, Abrechnungsmodelle und Supportprozesse. Das erhöht die operative Komplexität, erfordert spezialisierte Skills und belastet die Organisation.

Selbst grosse Organisationen wie das BIT stossen hier an Grenzen, sowohl personell als auch finanziell. Erfahrungsgemäss lässt sich eine Umgebung mit mehr als drei aktiven Cloudanbietern kaum effizient und sicher betreiben. Alles darüber hinaus erzeugt mehr Koordinationsaufwand, höhere Betriebskosten und längere Entscheidungswege.

Die Realität – Weniger ist oft mehr

Tatsächlich zeigt sich aber, dass der Bund heute mehrheitlich nur zwei der fünf Public-Cloud-Anbieter regelmässig nutzt.

Das wirft Fragen auf: Handelt es sich um eine technische Notwendigkeit, weil bestimmte Anforderungen nur von diesen Anbietern erfüllt werden können? Oder sind es bestehende Projekte, Partnerschaften und persönliche Präferenzen der Entscheidungsträger, die zu einer faktischen Konzentration führen?

Auch die Leistungsbezüger selbst, also die Ämter und Organisationen, die die Cloud-Leistungen abrufen, spielen hier eine Rolle. Oft sind externe Firmen in Body-Leasing- oder Beratungsmandaten eingebunden, die mit ihren Erfahrungen, Tools und Partnerschaften die Entscheidungspfade beeinflussen.

So kann ein Muster entstehen: Statt Vielfalt auf allen Ebenen zu leben, etabliert sich eine Kerngruppe an bevorzugten Anbietern, mit denen man “eingespielt” ist.

Das sind die offenen Geheimnisse, welche man in der Informatikbranche kennt. Dieses potenzielle Szenario und Risiko kann also überall auftreten, nicht nur beim Bund.

Theorie trifft Praxis und der Preis bleibt Nebensache

Selbst mit einem formal korrekten, anbieterneutralen Pflichtenheft und einem objektiven Kriterienkatalog kann das Ergebnis am Ende stark von den ursprünglichen Erwartungen abweichen.

Ein fiktives Beispiel: In einer Ausschreibung erfüllen mehrere Anbieter alle technischen und sicherheitsrelevanten Anforderungen. Einer davon liegt preislich rund 50% unter dem bevorzugten Anbieter und das in einer Zeit, in der vielerorts kritisiert wird, dass Public Cloud zu teuer sei und die grossen Hyperscaler das “Böse” verkörpern.

Trotzdem entscheidet man sich für den teureren Anbieter. Offiziell mag das durch andere Bewertungskriterien gedeckt sein, in der Praxis aber zeigt es, dass bestehende Präferenzen, bekannte Ökosysteme oder der Wunsch nach minimalem Umstellungsaufwand oft schwerer wiegen als reine Wirtschaftlichkeit.

Wie vendorneutral sind Pflichtenhefte wirklich?

Auf dem Papier klingt das Verfahren vorbildlich. Ein anbieterneutrales Pflichtenheft wird erstellt, ergänzt durch einen detaillierten Kriterienkatalog. Dort finden sich wohl Kriterien zu Themen wie zum Beispiel Compute, Storage, Netzwerk, Identity und Access Management, DevOps, und IT-Security.

In der Praxis bleibt jedoch die Frage: Wie “neutral” sind diese Pflichtenhefte tatsächlich formuliert? Oft werden technische Anforderungen so gesetzt, dass sie implizit bestimmte Anbieter bevorzugen. Nicht zwingend absichtlich, aber basierend auf bisherigen Projekten, vorhandenen Skills oder bekannten Plattformen.

Für den nicht involvierten Anbieter bleibt der Prozess eine Blackbox und bekommt am Ende wohl lediglich den Hinweis: „Ein anderer Anbieter hat die Anforderungen besser oder vollständiger erfüllt.“ Ohne das Pflichtenheft jemals gesehen zu haben, ohne den direkten Austausch mit dem Kunden (Bedarfsträger), und ohne zu wissen, ob einzelne Kriterien vielleicht auf Technologien zugeschnitten waren, die man selbst gar nicht im Portfolio hat.

Das Resultat ist eine formell korrekte, aber in der Wirkung oft unausgewogene und unfaire Auswahl.

Ist natürlich auch kein transparenter Prozess für den Steuerzahler, da auch keine öffentlichen Dokumente dazu existieren.

Fazit

Vielfalt ist kein Selbstzweck. Im Cloud-Kontext bedeutet sie nicht automatisch mehr Sicherheit oder Flexibilität. Manchmal sogar das Gegenteil. Entscheidend ist nicht, wie viele Anbieter theoretisch verfügbar sind, sondern wie gut die genutzten Anbieter in die strategischen Ziele passen und wie konsequent Modernisierung umgesetzt wird.

Die SGC bietet die Chance, beides zu verbinden: eine überschaubare, operativ beherrschbare Anbieterlandschaft und eine Plattform, die nicht nur heutigen Anforderungen genügt, sondern auch zukünftige Entwicklungen antizipiert.

Aber die Auswahl der Cloudanbieter soll auch fair passieren.

Hier geht es zum dritten Teil: Die versteckte Innovationsbremse in der Bundes-IT