Open source gives you freedom. Nutanix makes that freedom actually usable.

Every organisation that wants to modernise its infrastructure eventually arrives at the same question: How open should my cloud be? Not open as in “free and uncontrolled”, but open as in transparent, portable, verifiable. Open as in “I want to reduce my dependencies, regain autonomy and shape my architecture based on principles”.

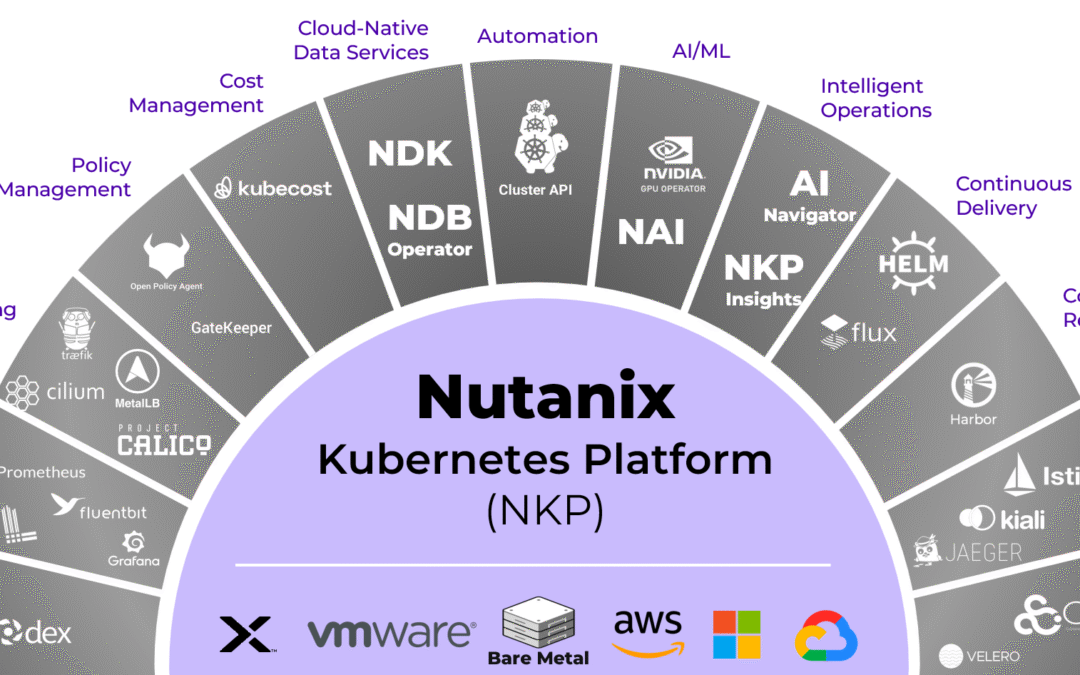

What most CIOs and architects have realized over time is that sovereignty and openness are not separate ideas. They depend on each other. And this is where Nutanix has become one of the most interesting players in the market. Because while many vendors talk about optionality, Nutanix has built a platform that is literally assembled out of open-source building blocks. That means curated, hardened, automated and delivered as a consistent experience.

It’s a structured open-source universe, integrated from day one and continuously maintained at enterprise quality.

In other words, Nutanix operationalizes open source, turning it into something teams can deploy, trust and scale without drowning in complexity.

Operationalizing Open Source

Every architect knows that adopting open source at scale is not trivial. The problem is not the software. The problem is the operational burden:

- Which projects are stable?

- Which versions are interoperable?

- Who patches them?

- Who maintains the lifecycle?

- How do you standardize the cluster experience across sites, regions, and teams?

- How do you avoid configuration drift?

- How do you keep performance predictable?

Nutanix solves this by curating the stack, integrating the components and automating the entire lifecycle. Nutanix Kubernetes Platform (NKP) is basically a “sovereignty accelerator”. It enables organizations to adopt a fully open ecosystem while maintaining the reliability and simplicity that enterprises require.

A Platform Built on Upstream Open Source

What often gets overlooked in the cloud-native conversation is that open source is not a single entity. There is upstream open source, which can be seen as the pure, community-driven version. And then there are vendor-modified forks, custom APIs, and platforms that quietly redirect you into proprietary interfaces the moment you start building something serious.

Nutanix took a very different path. NKP is built on pure upstream open-source components. Not repackaged, not modified into proprietary variants, not wrapped in a “special” vendor API that locks you in. The APIs exposed to the user are the same APIs used everywhere in the CNCF community.

This matters more than most people realize.

Because the moment a vendor alters an API, you lose portability. And the moment you lose portability, you lose sovereignty.

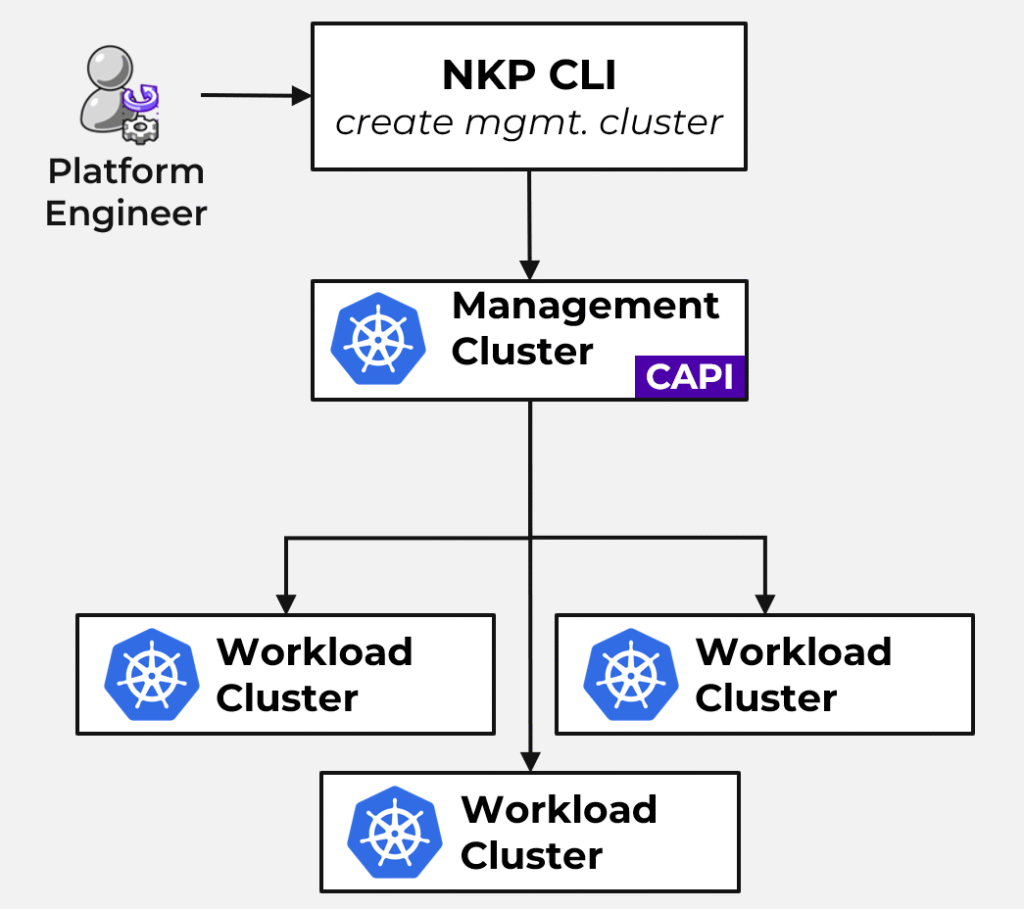

One of the strongest signals that Nutanix also prioritizes sovereignty, is its commitment to Cluster API (CAPI). This is what gives NKP deployments the portability many vendors can only talk about.

With CAPI, the cluster lifecycle (creation, upgrade, scaling, deletion) is handled through a common, open standard that works:

- on-premises & baremetal

- on Nutanix

- on AWS, Azure or GCP

- in other/public sovereign cloud regions

- at the edge

CAPI means your clusters are not married to your infrastructure vendor.

Nutanix Entered the Gartner MQ for Container Management 2025

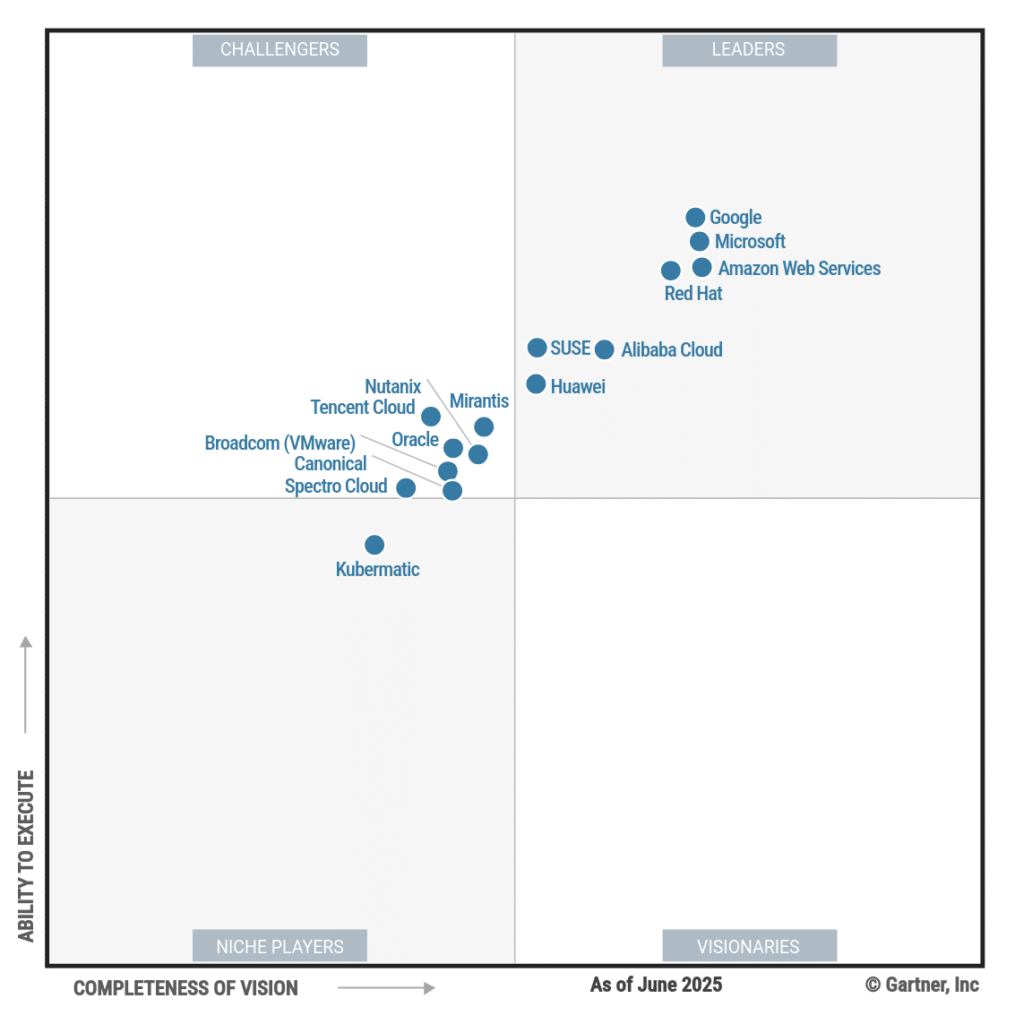

Every Gartner Magic Quadrant tells a story. Not just about vendors, but about the direction a market is moving. And the 2025 Magic Quadrant for Container Management is particularly revealing. Not only because Nutanix appears in it for the first time, but because of where Nutanix is positioned and what that position says about the future of cloud-native platforms.

Nutanix made its debut as a Challenger and that’s probably a rare achievement for a first-time entrant. Interestingly and more importantly, Nutanix positioned above Broadcom (VMware) on both axes:

- Ability to execute

- Completeness of vision

2025 marks a new landscape – Broadcom fell out of the leaders quadrant entirely and now lags behind Nutanix in both execution and vision. This reflects a broader transition in customer expectations.

Organizations want portability, sovereign deployment models, and platforms that behave like products rather than collections of components. Nutanix delivered exactly that with NKP and gets recognized for that.

When Openness Becomes Strategy, Sovereignty Becomes Reality

If you step back and look at all the signals, from the rise of sovereign cloud requirements to the changes reflected in Gartner’s latest Magic Quadrant, a clear pattern emerges. The market is moving away from closed ecosystems, inflexible stacks and proprietary abstractions.

Vision today is no longer defined by how many features you can stack on top of Kubernetes. Vision is defined by how well you can make Kubernetes usable, secure, portable and sovereign. In the data center, at the edge, in public clouds, or in fully disconnected/air-gapped environments.