Disclaimer: This article reflects my personal opinion and not that of my employer.

The discussion around a Swiss Government Cloud (SGC) has gained significant momentum in recent months. Digital sovereignty has become a political and technological necessity with immediate relevance. Government, politics, and industry are increasingly asking how a national cloud infrastructure could look. This debate is not just about technology, but also about governance, funding, and the ability to innovate.

Today’s starting point is relatively homogeneous. A significant portion of Switzerland’s public sector IT infrastructure still relies on VMware. This setup is stable but not designed for the future. When we talk about the Swiss Government Cloud, the real question is how this landscape evolves from pragmatic use of the public cloud to the creation of a fully sovereign cloud, operated under Swiss control.

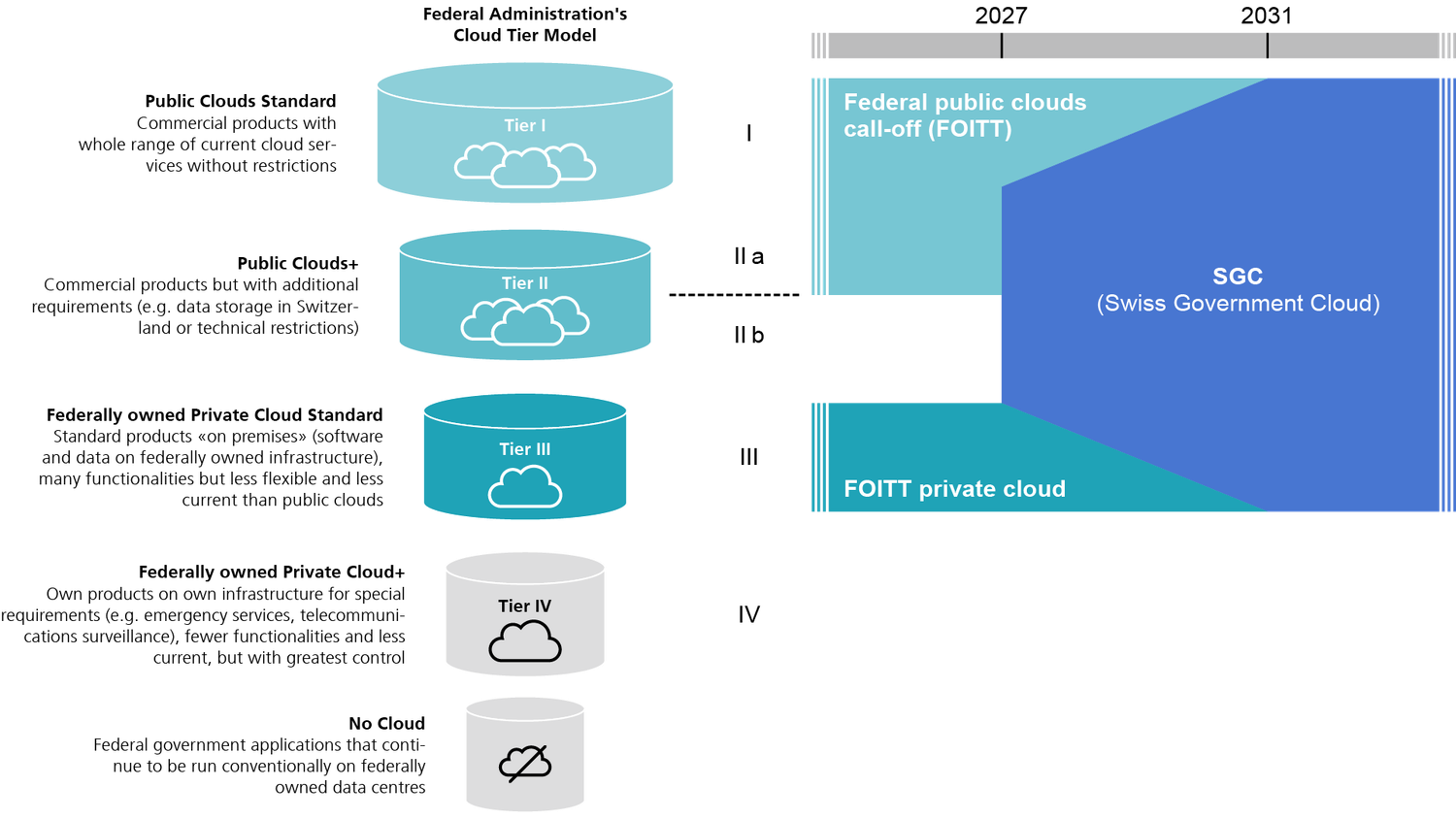

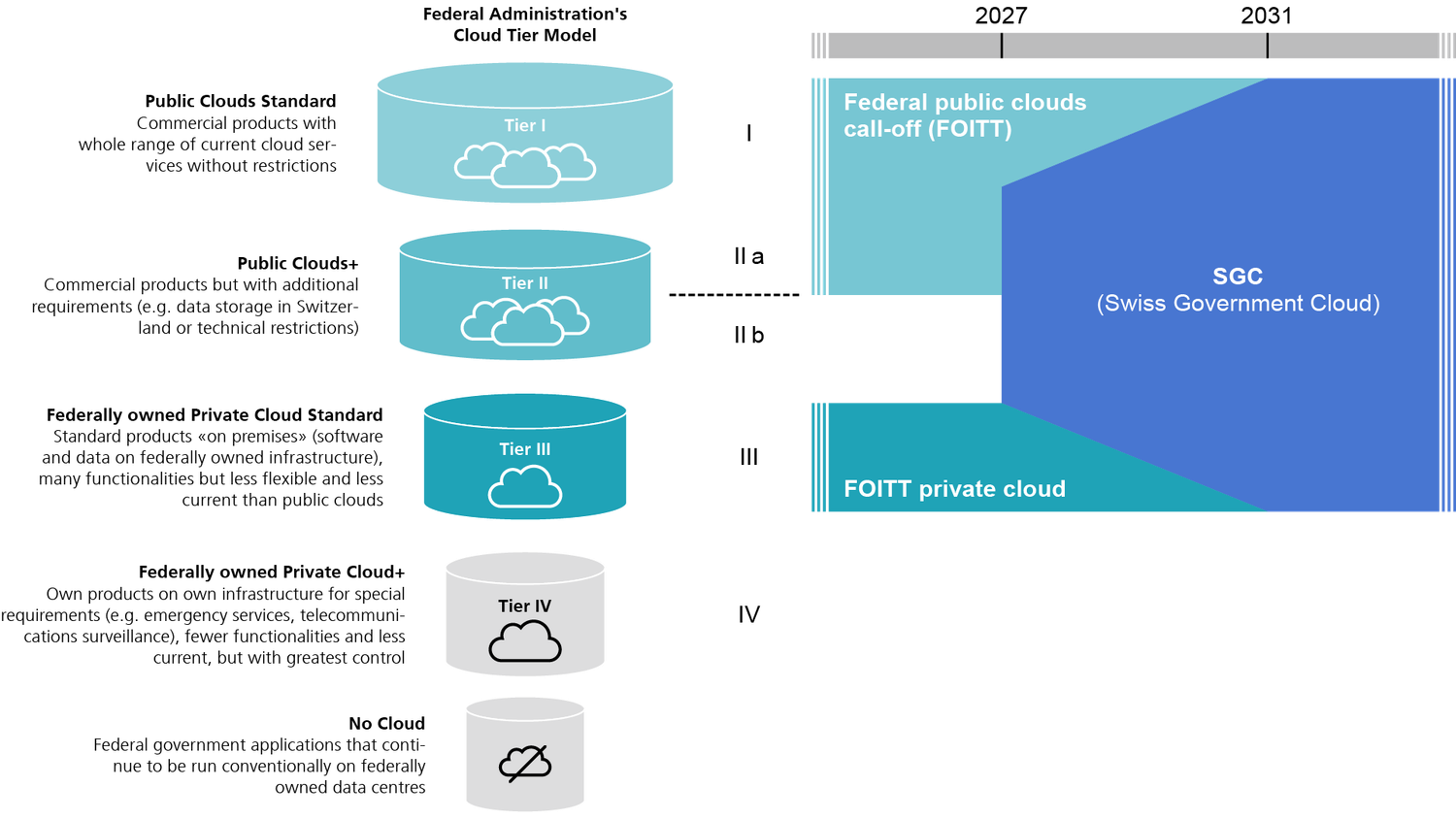

For clarity: I use the word “component” (Stufe), in line with the Federal Council’s report, to describe the different maturity levels and deployment models.

A Note on the Federal Council’s Definition of Digital Sovereignty

According to the official report, digital sovereignty includes:

-

Data and information sovereignty: Full control over how data is collected, stored, processed, and shared.

-

Operational autonomy: The ability of the Federal Office of Information Technology (FOITT) to run systems with its own staff for extended periods, without external partners.

-

Jurisdiction and governance: Ensuring that Swiss law, not foreign regulation, defines control and access.

This definition is crucial when assessing whether a cloud model is “sovereign enough.”

Component 1 – Public Clouds Standard

The first component describes the use of the public cloud in its standard form. Data can be stored anywhere in the world, but not necessarily in Switzerland. Hyperscalers such as AWS, Microsoft Azure, or Oracle Cloud Infrastructure (OCI) offer virtually unlimited scalability, the highest pace of innovation, and a vast portfolio of services.

Amazon Web Services (AWS) is the broadest platform by far, providing access to an almost endless variety of services and already powering workloads from MeteoSwiss.

Microsoft Azure integrates deeply with Microsoft environments, making it especially attractive for administrations that are already heavily invested in Microsoft 365 and MS Teams. This ecosystem makes Azure a natural extension for many public sector IT landscapes.

Oracle Cloud Infrastructure (OCI), on the other hand, emphasizes efficiency and infrastructure, particularly for databases, and is often more transparent and predictable in terms of cost.

However, component 1 must be seen as an exception. For sovereign and compliant workloads, there is little reason to rely on a global public cloud without local residency or control. This component should not play a meaningful role, except in cases of experimental or non-critical workloads.

And if there really is a need for workloads to run outside of Switzerland, I would recommend using alternatives like the Oracle EU Sovereign Cloud instead of a regular public region, as it offers stricter compliance, governance, and isolation for European customers.

Component 2a – Public Clouds+

Here, hyperscalers offer public clouds with Swiss data residency, combined with additional technical restrictions to improve sovereignty and governance.

AWS, Azure, and Oracle already operate cloud regions in Switzerland today. They promise that data will not leave the country, often combined with features such as tenant isolation or extra encryption layers.

The advantage is clear. Administrations can leverage hyperscaler innovation while meeting legal requirements for data residency.

Component 2b – Public Cloud Stretched Into FOITT Data Centers

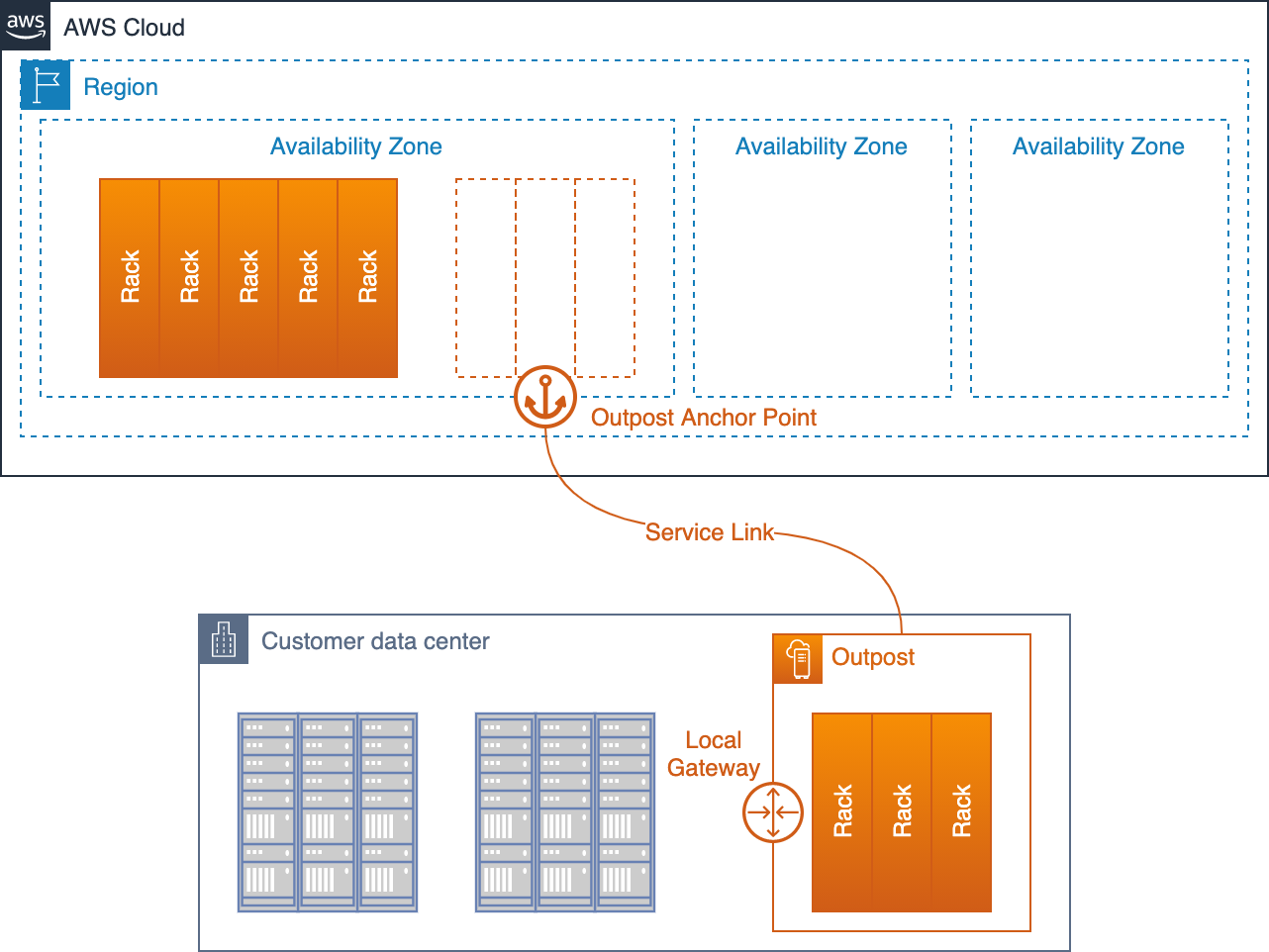

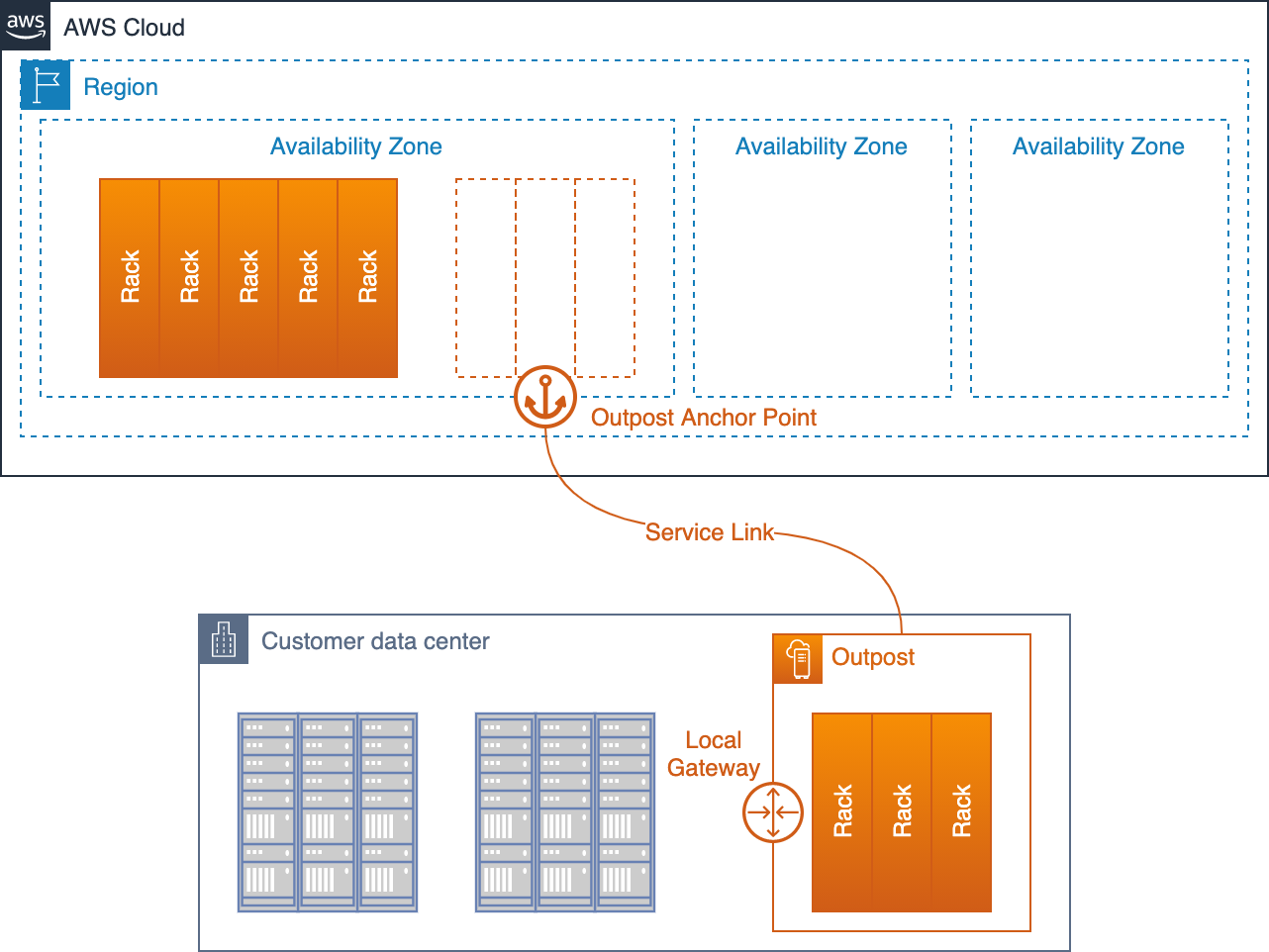

This component goes a step further. Here, the public cloud is stretched directly into the local data centers. In practice, this means solutions like AWS Outposts, Azure Local (formerly Azure Stack), Oracle Exadata & Compute Cloud@Customer (C3), or Google Distributed Cloud deploy their infrastructure physically inside FOITT facilities.

This creates a hybrid cloud. APIs and management remain identical to the public cloud, while data is hosted directly by the Swiss government. For critical systems that need cloud benefits but under strict sovereignty (which differs between solutions), this is an attractive compromise.

The vendors differ significantly:

Costs and operations are predictable since most of these models are subscription-based.

Component 3 – Federally Owned Private Cloud Standard

Not every path to the Swiss Government Cloud requires a leap into hyperscalers. In many cases, continuing with VMware (Broadcom) represents the least disruptive option, providing the fastest and lowest-risk migration route. It lets institutions build on existing infrastructure and leverage known tools and expertise.

Still, the cloud dependency challenge isn’t exclusive to hyperscalers. Relying solely on VMware also creates a dependency. Whether with VMware or a hyperscaler, dependency remains dependency and requires careful planning.

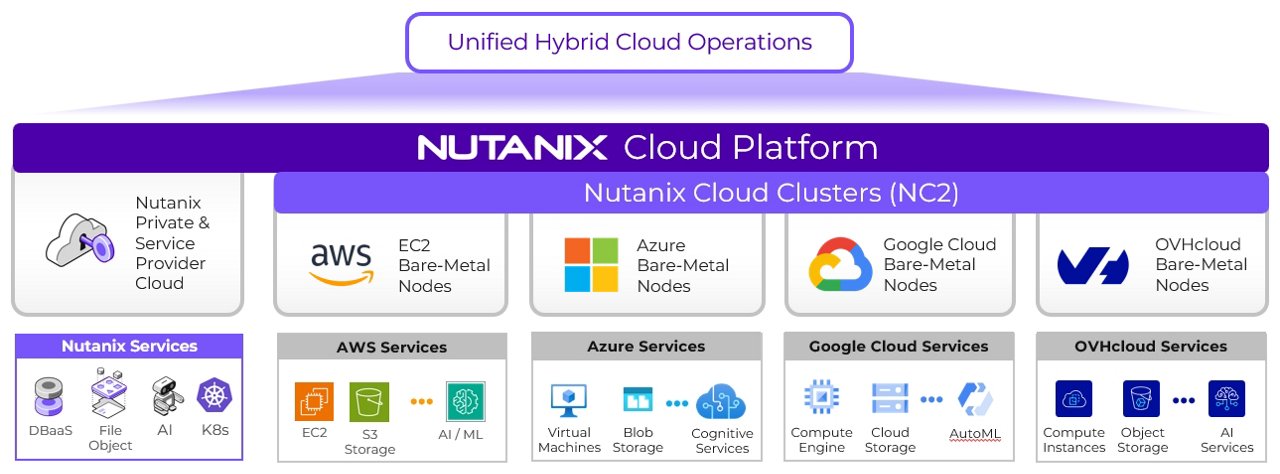

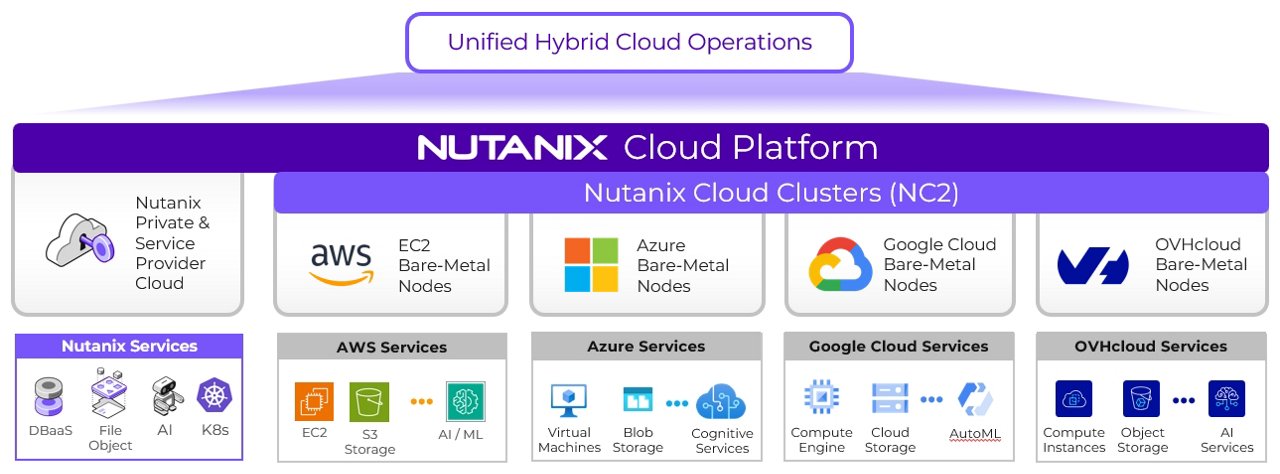

Another option is Nutanix, which offers a modern hybrid multi-cloud solution with its AHV hypervisor. However, migrating from VMware to AHV is in practice as complex as moving to another public cloud. You need to replatform, retrain staff, and become experts again.

Both VMware and Nutanix offer valid hybrid strategies:

-

VMware: Minimal disruption, continuity, familiarity, low migration risk. Can run VMware Cloud Foundation (VCF) on AWS, Azure, Google Cloud and OCI.

-

Nutanix: Flexibility and hybrid multi-cloud potential, but migration is similar to changing cloud providers.

Crucially, changing platforms or introducing a new cloud is harder than it looks. Organizations are built around years of tailored tooling, integrations, automation, security frameworks, governance policies, and operational familiarity. Adding or replacing another cloud often multiplies complexity rather than reduces it.

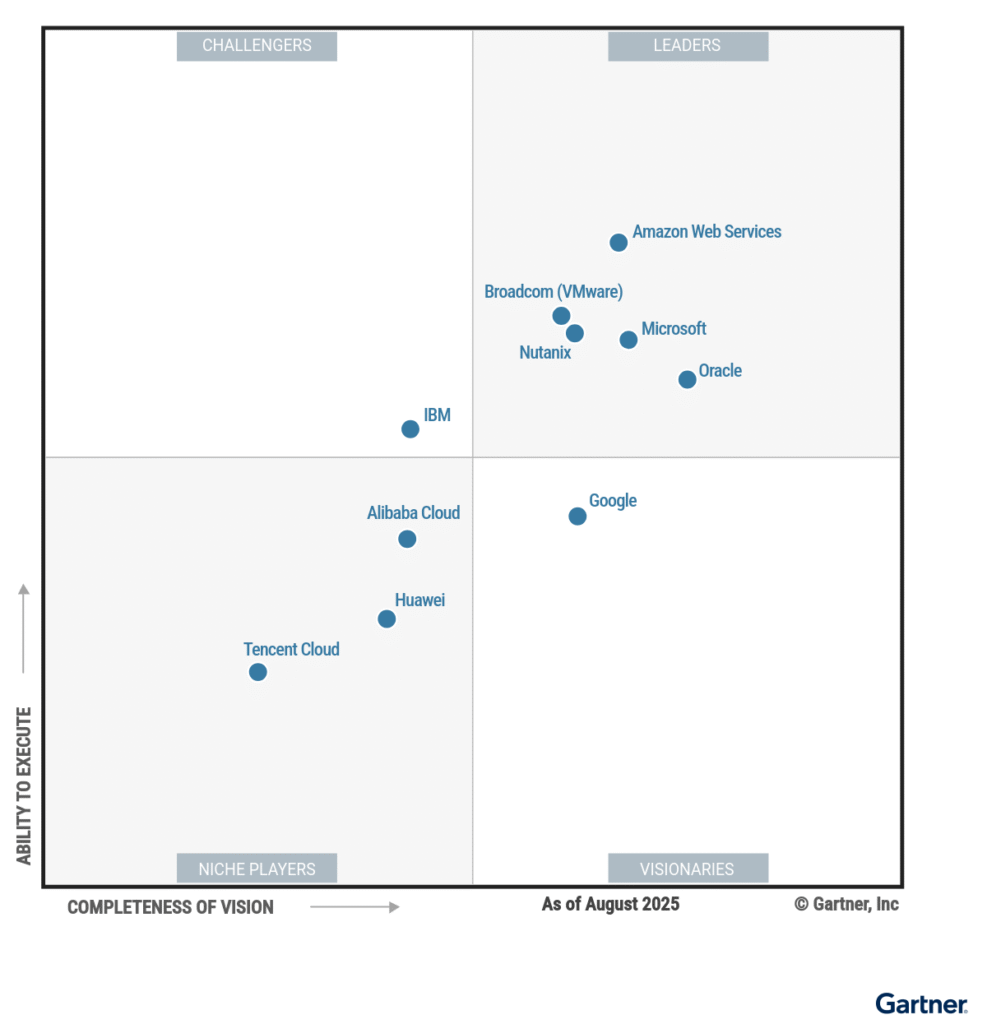

Source: https://www.oracle.com/uk/cloud/distributed-cloud/gartner-leadership-report/

But sometimes it is just about costs, new requirements, or new partnerships, which result in a big platform change. Let’s see how the Leaders Magic Quadrant for “Distributed Hybrid Infrastructure” changes in the coming weeks or months.

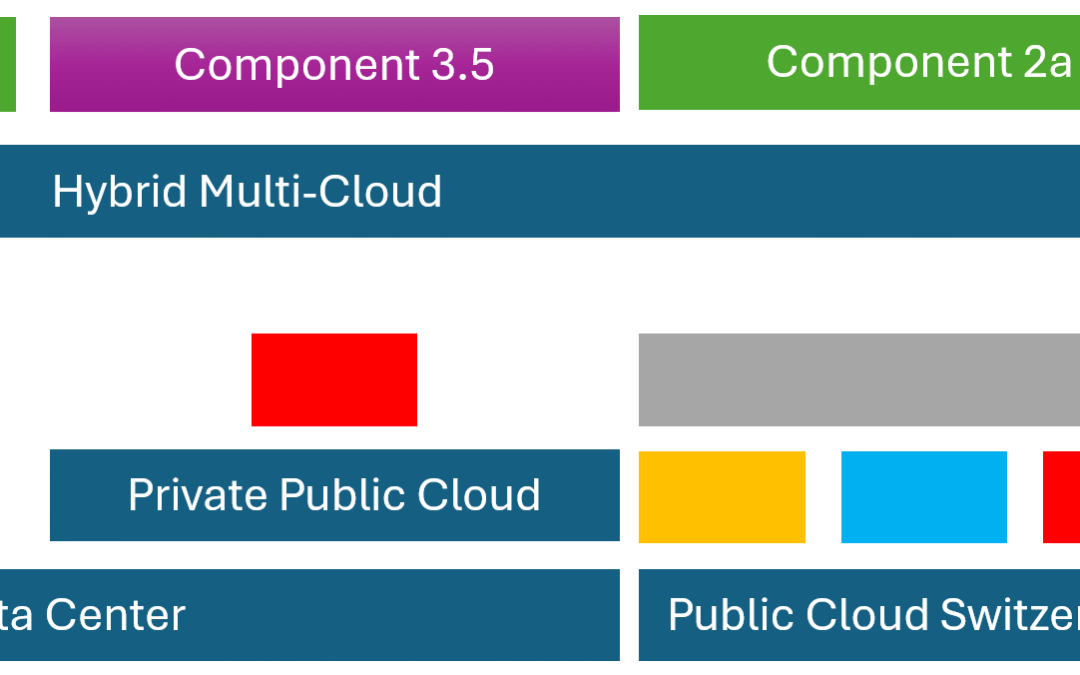

Why Not Host A “Private Public Cloud” To Combine Components 2 and 3?

This possibility (let’s call with component 3.5) goes beyond the traditional framework of the Federal Council. In my view, a “private public cloud” represents the convergence of public cloud innovation with private cloud sovereignty.

“The hardware needed to build on-premises solutions should therefore be obtained through a ‘pay as you use’ model rather than purchased. A strong increase in data volumes is expected across all components.”

Source: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/fga/2024/1408/de#lvl_2/lvl_2.4 (translated from German)

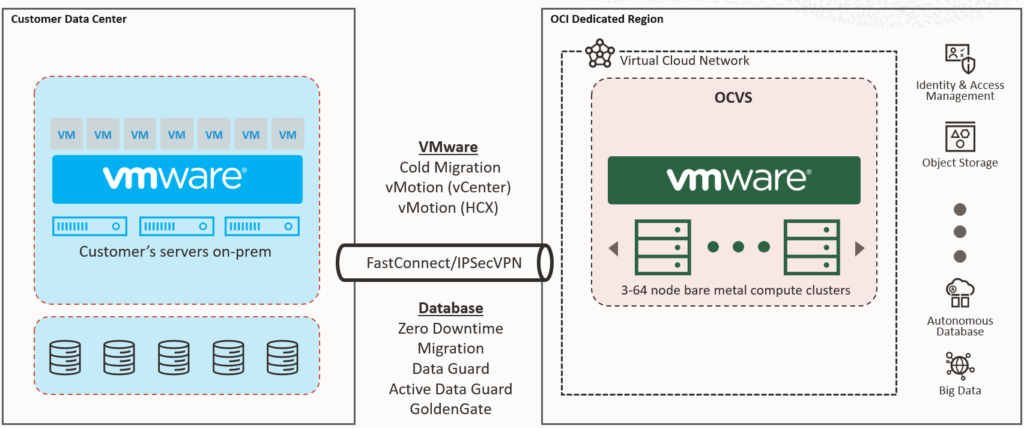

Solutions like OCI Dedicated Region or Oracle Alloy can deliver the entire Oracle Cloud stack– IaaS, PaaS, databases, analytics – on Swiss soil. Unlike AWS Outposts, Azure Local, these solutions are not coming with a limited set of cloud services, but are identical to a full public cloud region with all cloud services, only hosted and operated locally in a customer’s data center.

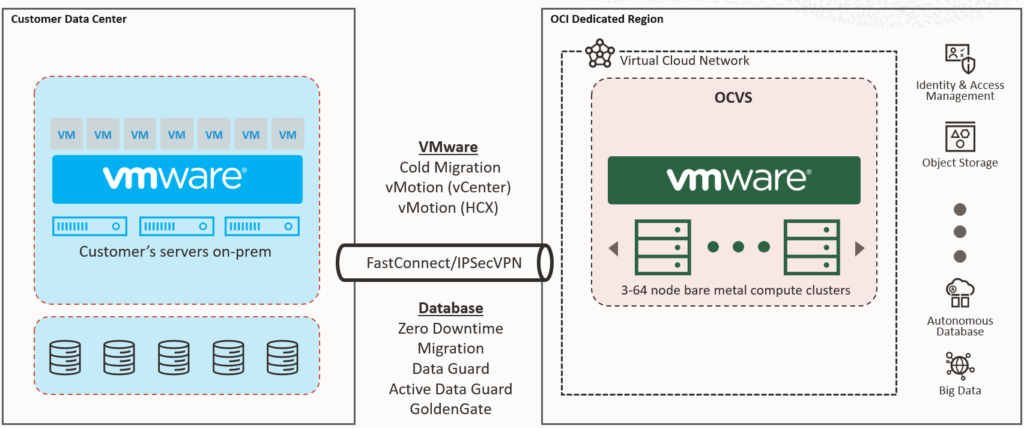

Additionally, Oracle offers a compelling hybrid path. With OCVS (Oracle Cloud VMware Solution) on OCI Dedicated Region or Alloy, organizations can lift-and-shift VMware workloads unchanged to this local public cloud based on Oracle Cloud Infrastructure, then gradually modernize selected applications using Oracle’s PaaS services like databases, analytics, or AI.

This “lift-and-modernize” journey helps balance risk and innovation while ensuring continuous operational stability.

And this makes component 3.5 unique. It provides the same public-cloud experience (continuous updates, innovation pace; 300-500 changes per day, 10’000-15’000 per month) but under sovereign control. With Alloy, the FOITT could even act as a Cloud Service Provider for cantons, municipalities, and hospitals, creating a federated model without each canton building its own cloud.

Real-world Swiss example: Avaloq was the first customer in Switzerland to deploy an OCI Dedicated Region, enabling it to migrate clients and offer cloud services to other banks in Switzerland. This shows how a private public cloud can serve highly regulated industries while keeping data and operations in-country.

In this model:

-

Component 2b becomes redundant: Why stretch a public cloud into FOITT data centers if a full cloud can already run there?

-

Component 2 can also be partly obsolete: At least for workloads running a local OCI Dedicated Region (or Alloy) deployment, there’s no need for parallel deployments in public regions, since everything can run sovereignly on a local dedicated OCI region in Switzerland (while workloads from MeteoSwiss on AWS remain in component 2).

A private public cloud thus merges sovereignty with innovation while reducing the need for parallel cloud deployments.

Another Possibility – Combine Capabilities From A Private Public Cloud With Component 2b

Another possibility could be to combine elements of components 3.5 and 2b into a federated architecture: Using OCI Dedicated Region or Oracle Alloy as the central control plane in Switzerland, while extending the ecosystem with Oracle Compute Cloud@Customer (C3) for satellite or edge use cases.

This creates a hub-and-spoke model:

-

The Dedicated Region or Alloy in Switzerland acts as the sovereign hub for governance and innovation.

-

C3 appliances extend cloud services into distributed or remote locations, tightly integrated but optimized for local autonomy.

A practical example would be Swiss embassies around the world. Each embassy could host a lightweight C3 edge environment, connected securely back to the central sovereign infrastructure in Switzerland. This ensures local applications run reliably, even with intermittent connectivity, while remaining part of the overall sovereign cloud ecosystem.

By combining these capabilities, the FOITT could:

-

Use component 2b’s distributed deployment model (cloud stretched into local facilities)

-

Leverage component 3.5’s VMware continuity path with OCVS for easy migrations

-

Rely on component 3.5’s sovereignty and innovation model (private public cloud with full cloud parity)

This blended approach would allow Switzerland to centralize sovereignty while extending it globally to wherever Swiss institutions operate.

What If A Private Public Cloud Isn’t Sovereign Enough?

It is possible that policymakers or regulators could conclude that solutions such as OCI Dedicated Region or Oracle Alloy are not “sovereign enough”, given that their operational model still involves vendor-managed updates and tier-2/3 support from Oracle.

In such a scenario, the BIT would have fallback options:

Maintain a reduced local VMware footprint: BIT could continue to run a smaller, fully local VMware infrastructure that is managed entirely by Swiss staff. This would not deliver the breadth of services or pace of innovation of a hyperscale-based sovereign model, but it would provide the maximum possible operational autonomy and align closely with Switzerland’s definition of sovereignty.

Leverage component 4 from the FDJP: Using the existing “Secure Private Cloud” (SPC) from the Federal Department of Justice and Police (FDJP). But I am not sure if the FDJP wants to become a cloud service provider for other departments.

That said, these fallback strategies don’t necessarily exclude the use of OCI. Dedicated Region or Alloy could co-exist with a smaller VMware footprint, giving the FOITT both innovation and control. Alternatively, Oracle could adapt its operating model to meet Swiss sovereignty requirements – for example, by transferring more operational responsibility (tier-2 support) to certified Swiss staff.

This highlights the core dilemma: The closer Switzerland moves to pure operational sovereignty, the more it risks losing access to the innovation and agility that modern cloud architectures bring. Conversely, models like Dedicated Region or Alloy can deliver a full public cloud experience on Swiss soil, but they require acceptance that some operational layers remain tied to the vendor.

Ultimately, the Swiss Government Cloud must strike a balance between autonomy and innovation, and the decision about what “sovereign enough” means will shape the entire strategy.

Conclusion

The Swiss Government Cloud will not be a matter of choosing one single path. A hybrid approach is realistic: Public cloud for agility and non-critical workloads, stretched models for sensitive workloads, VMware or Nutanix for hybrid continuity, sovereign or “private public cloud” infrastructures for maximum control, and federated extensions for edge cases.

But it is important to be clear: Hybrid cloud or even hybrid multi-cloud does not automatically mean sovereign. What it really means is that a sovereign cloud must co-exist with other clouds – public or private.

To make this work, Switzerland (and each organization within it) must clearly define what sovereignty means in practice. Is it about data and information sovereignty? Is it really about operational autonomy? Or about jurisdiction and governance?

Only with such a definition can a sovereign cloud strategy deliver on its promise, especially when it comes to on-premises infrastructure, where control, operations, and responsibilities need to be crystal clear.

PS: Of course, the SGC is about much more than infrastructure. The Federal Council’s plan also touches networking, cybersecurity, automation and operations, commercial models, as well as training, consulting, and governance. In this article, I deliberately zoomed in on the infrastructure side, because it’s already big, complex, and critical enough to deserve its own discussion. And just imagine sitting on the other side, having to go through all the answers of the upcoming tender. Not an easy task.